When I travel, my thoughts and eyes are always drawn to the history of the area that I am now exploring. Old buildings, road names, heritage markers, interpretive signs, museums and the like always capture my interest and curiosity.

Having recently spent some vacation time in the Port Elgin area, the trip offered me yet another chance to ponder and wonder what was around me – and to see if I could find Mississauga connections, if any. I am always enamoured by that process of connecting wherever I might be to the place I call home.

Hiking along the “Old Shore Road” trail in MacGregor Point Provincial Park had me thinking of historic routes of travel.

The trail is a former right-of-way, having faded in use and into obscurity, and now repurposed as a recreational hiking trail. This old route had been, over time, superseded and replaced by a new (and straighter) route of travel, further inland. What is left today is but a reminder of what it once was. But what of our own “old routes”? Do they still show on the landscape here in Mississauga?

A quick mental perusal confirmed that many still exist in our city: Dundas Street and Lakeshore Road still follow their historic paths, which themselves, in part, shadow earlier Indigenous trails, as does modern Mississauga Road, Stavebank Road, and Old Carriage Road (and those names offer yet more clues to our past!).

Our history routes of travel have not, for the most part, faded in importance such as the “Old Shore Road”. But both the modern thoroughfare and a historic path can play a significant role in “rooting” our landscape in both the past and present.

In my travels around Port Elgin, we fell in love with a charming area called Gobles Grove along Saugeen Beach Road – truly a beautiful area – but the road itself, and particularly where the wave action of Lake Huron had damaged part of the road – had me thinking about former roads in our community that have been impacted by the water.

Boustead Terrace in Lorne Park was claimed by the lake many years ago, and Lake Street in Port Credit was “saved” only through the creation of Saddington Park. People and place have always had an uneasy, but dependent, relationship with the water.

Watching the sunset at the pier in nearby Southampton one evening was a magical experience – particularly for those, like myself, who see more sunrises than sunsets. As the fiery ball sank lower on the horizon over Lake Huron, the silhouette of the historic Chantry Island Lightstation Tower invariably drew my gaze.

Built in 1859, the Chantry Island lighthouse was one of six Imperial lighthouses built to guide marine traffic on Lake Huron and Georgian Bay. Back on the shores of historic Mississauga, efforts were also underway around the same time to ease the challenges of traversing Lake Ontario.

The first attempt to light the harbour at Port Credit came in 1863 when a lantern was reportedly hung from a warehouse along the dock. In 1882 our first permanent lighthouse was built at the end of a pier, guiding travellers to the safety of Port Credit’s harbour.

Different in scale and construction than the grand Imperial towers, the little wooden lighthouse at Port Credit played the same role as the Chantry Island lighthouse in the lives of those who plied the temperamental waters of the lake.

The lighthouse on Chantry Island just off of Southampton overlooks some of Lake Huron’s deadliest shoals, claiming more than 50 shipwrecks. Reportedly among them is the Enterprise, a wooden schooner built in Port Credit around 1864 by Alexander Blakeley.

In 1902 the Enterprise was purchased by the Georgian Bay Navigation Company, and began sailing out of Collingwood in the transport of cedar posts. In September of 1930 she was lost off of Southampton during a gale, reportedly within view of the Chantry Island lighthouse – a Port Credit-built schooner lies in the waters of Lake Huron near Southampton, having traversed the Great Lakes for almost 70 years.

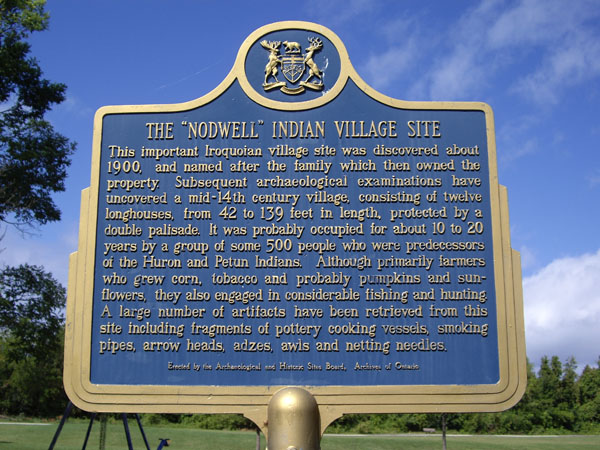

Another site I visited also brought to mind our history here in Mississauga. In the centre of Port Elgin there is an Ontario Heritage Trust plaque remembering the “Nodwell” Indian Village site.

This important Iroquoian village site was discovered about 1900, and named after the family which then owned the property. Subsequent archaeological examinations have uncovered a mid-14th century village, consisting of twelve longhouses, from 42 to 139 feet in length, protected by a double palisade.

It was probably occupied for about 10 to 20 years by a group of some 500 people who were predecessors of the Huron and Petun Indians. Although primarily farmers who grew corn, tobacco and probably pumpkins and sunflowers, they also engaged in considerable fishing and hunting. A large number of artifacts have been retrieved from this site including fragments of pottery cooking vessels, smoking pipes, arrow heads, adzes, awls and netting needles.

The linkage to a “vanished” part of a community’s heritage and early Indigenous history is not dissimilar to the story of the Credit Mission Village site, or other, even earlier, archaeological sites within our city.

Yes, we also have a complex and multi-layered history spanning thousands of years of people on the landscape of what is now the City of Mississauga – as does Port Elgin and countless other communities in our country. Our early settlers did not “settle” on empty land.

Although the links between Saugeen Shores and Mississauga are indirect, it is impossible (at least for me) to traverse those scenic shoreline routes and not be drawn to reflecting on links to our modern landscapes here in Mississauga; links that speak to our Indigenous, marine and settler roots – both here and there, wherever “there” may be.

Comments are closed.