Outrage at the news from the Kamloops Indian Residential School. A statue toppled. The anger is palpable. Sadly the story is not a new one, and unfortunately it is likely a story that we will hear again … and again. The road to healing, of reconciling our history with finding a path forward, will be a difficult road to come to terms with.

This article is not intended to be a treatise on the story of Egerton Ryerson or the residential school system. Rather, it is this historian’s attempt to grapple with the subject even as my own understanding is evolving.

I have always believed that history plays a significant role in developing a sense of place, of “rootedness”, of caring about the place in which you live, and in that, the exploration and celebration of our heritage plays a significant role in developing and strengthening a sense of community. I believe that still.

But history is not a static thing. The study of our past, and our current connections to that history, evolves, just as our society evolves.

We look at things with new eyes and new perspectives over successive generations and an ever-changing sense of identity. Heritage is a living, breathing thing.

Collectively in this country we are in the midst of a long-coming review, and re-interpretation, of our colonial past.

Too often our history has been told through the lens of the settler-perspective.

There have been times in our collective past when our perspectives of who and what are significant, and how we honour and remember our past, has undergone drastic shifts.

Sir John A., Lord Dundas, Sir Simcoe, and Egerton Ryerson are not the first to be viewed in a changing light, nor will they be the last.

Anytime there has been a seismic shift in our societal relationship with long-held traditions (and narratives), it has taken time for the cultural discourse to find the new normal.

Author Deepak Bidwai wrote recently for the Ryersonian about the concept of “gatekeepers” – those individuals that either directly or indirectly informed and/or reinforced our colonial-era histories, often unintentionally, to the detriment of those who were outside of that colonial-focussed narrative.

Personally I know that I have been a “gatekeeper” of sorts, and unknowingly so, or perhaps unaware of my own colonial-informed and institutionally-ingrained perspectives.

I know that I am in the process of re-evaluating my own perceptions amidst the wider social discourse over the past many years.

There are, of course, many miles yet to travel on that road of understanding and reconciling our recorded stories through the lens of evolving perspectives.

I tend to view the debate over the roles of Egerton Ryerson, and others, in that light. We are in the process of critically reviewing their legacies – and rightfully so. In time, a new narrative will emerge that explores a broader scope.

We are not there yet.

The heartbreaking stories of residential schools have been with us for years, and for many people in our country, its legacy has shaped generations.

Just as our country has wonderful things to celebrate and honour, our Nation’s history is not without its dark chapters, such as our connections to slavery, Japanese-Canadian Internment, the Komagata Maru, and the Sixties Scoop, just to name a few.

Our job as historians today is to ensure that we give balanced thought to the multitude of layers of our history – even as our own understandings evolve.

Part of this evolution of understanding is re-exploring the history of our own community, which brings me back to the topic at hand: Egerton Ryerson and the former “Ryerson Road” here in Mississauga.

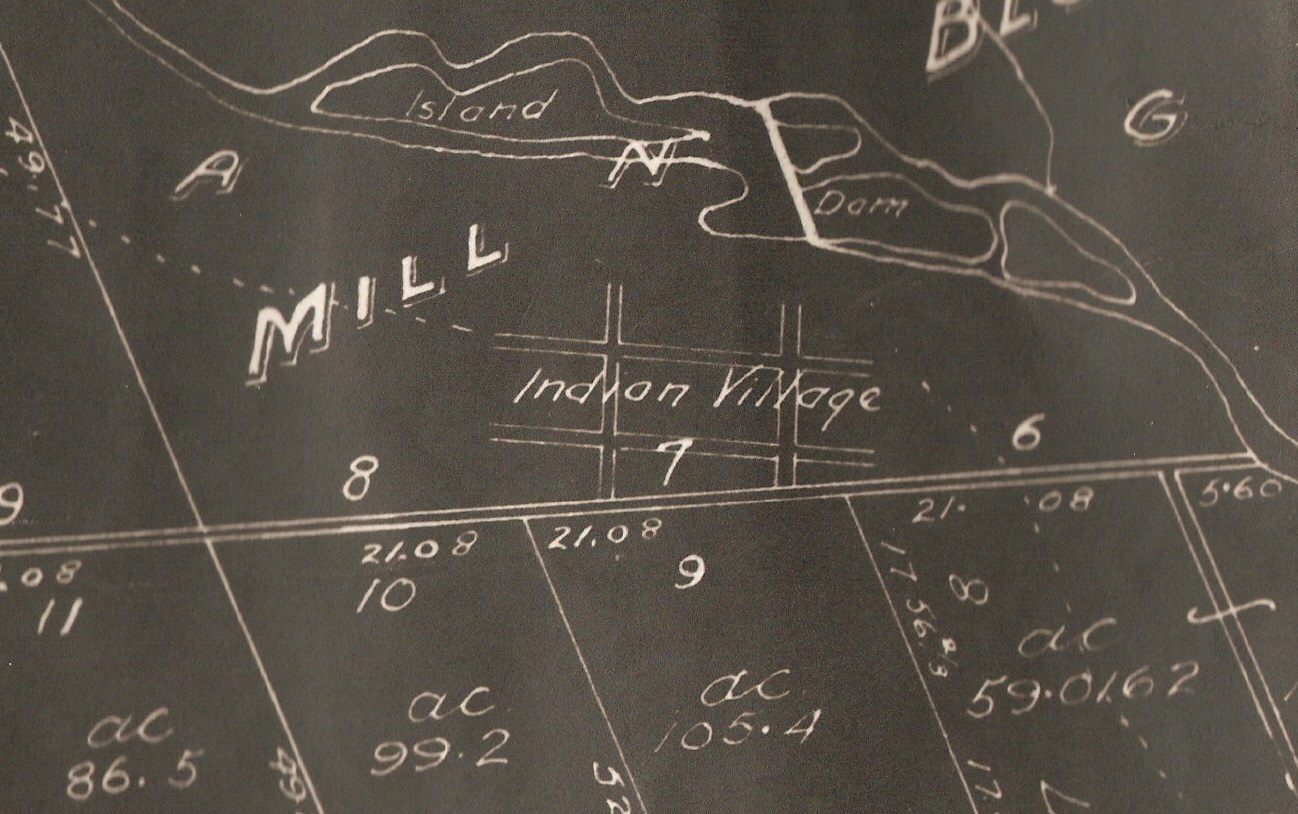

Did you know that we had a “Ryerson Road”? I did not know that until recently. The road was officially closed in 1931, and there is no evidence of the road on the landscape today.

Even old survey maps are hard to decipher. Ryerson Road was part of the Credit Mission Village, at what is today the Mississaugua Golf and Country Club on Mississauga Road.

The Credit Mission Village was laid out in 1826, but we do not know when the road acquired its name, or if it ever had a road sign indicating its name. Other than one map (a 1958 survey plan), we have not found any other references to the road name.

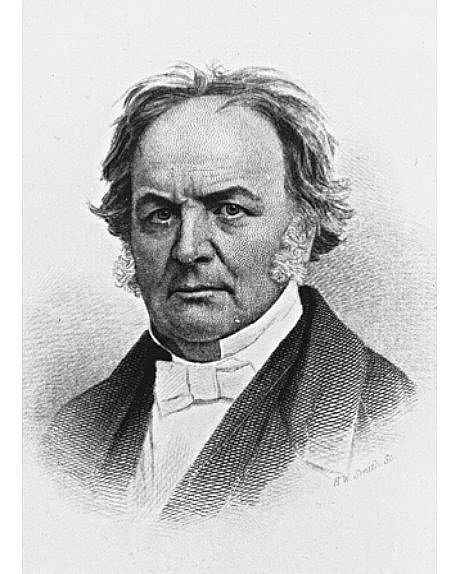

Given its location within the former Credit Mission Village site, the road was most likely named for Reverend Egerton Ryerson (1803-1882), who was, amongst other things, the Chief Superintendent of Education for Upper Canada from 1844 until 1876. In that position, in simple terms, he championed educational reforms, textbooks, and free public education.

Earlier in his career, Ryerson found himself posted to the Credit Mission Village, here in what is today the City of Mississauga. Ryerson, then a young 23-year-old minister, came to the Credit Mission as a Christian Methodist missionary in the fall of 1826.

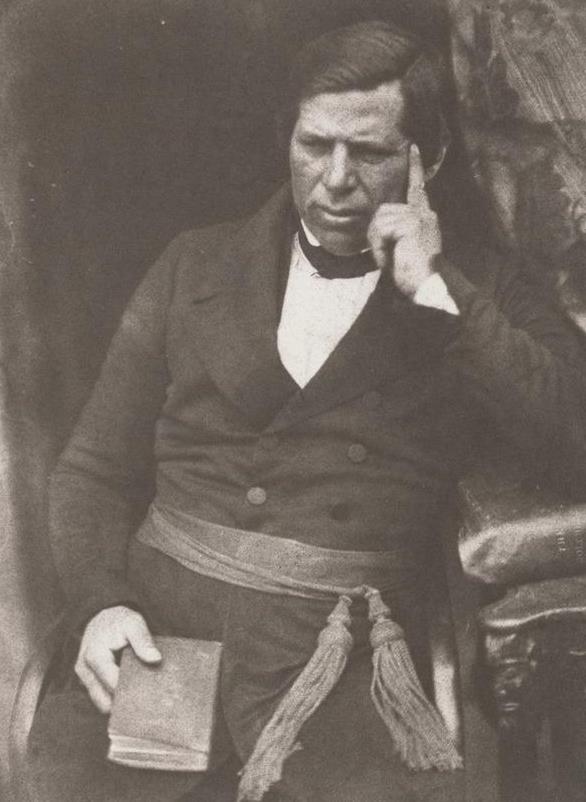

He had met Kahkewaquonaby, Reverend Peter Jones, previously. The two men developed a strong friendship. Jones was only a year older, and his friendship with Ryerson would last the rest of Jones’ life.

The Mississaugas of the Credit River came to respect Ryerson, as he made an effort to work alongside them and learn the Anishinaabe language.

Make no mistake, however, Ryerson was a Christian first, and the conversion of the Mississaugas to Christianity, the introduction of Christian education, and the teaching of modern farming techniques was the direct purpose behind his posting to the Credit Mission.

Ryerson was only at the Credit Mission for a year, but his presence resonated within the community he helped to shape during its first year of existence. His experience working amongst the Mississaugas, and his friendship with Jones, were also important building blocks in Ryerson’s own path.

In 1847, after Ryerson had been appointed as Chief Superintendent of Education for Upper Canada, the Assistant Superintendent General of Indian Affairs asked Ryerson to produce a report on the best methods for establishing and operating residential schools for Indigenous children.

The concept was not a new one.

Similar schools had existed elsewhere, and the Mohawk Institute Residential School in Brantford had been in operation since 1831.

The Bagot Commission of 1844 had recommended manual labour schools where Indigenous children would be separated from their parents.

Ryerson himself supported different systems of education for Indigenous students with the goal of assimilating them into the prevailing Euro-Canadian culture.

Ryerson’s 1847 report recommended that Indigenous children continue to be educated in separate, agricultural and industrial boarding schools with religious and English language instruction.

Students would be instructed in agriculture for two to three hours each day, and the rest of their studies would include academic subjects such as history, geography, writing, music, bookkeeping and agricultural chemistry.

A key for Ryerson, like so many of that time, was religious instruction. Ryerson proposed that schools be operated by religious organizations and overseen by the government. In short, the concept of residential schools was not created by Ryerson, although he certainly supported the plan.

His recommendations did influence the establishment of the residential school structure in Canada, although much of what was developed occurred after his death. One wonders how much of Ryerson’s concepts around residential schools might have been influenced by his short time spent here along the banks of the Credit River.

Ryerson, of course, was not alone in his thoughts around the potential benefits of residential schools. Many others supported the idea of introducing “civilization” and Christianity to Indigenous cultures. Many Indigenous leaders themselves supported this line of thinking, including, initially, Reverend Peter Jones.

The Credit Mission here in the City of Mississauga was not home to a residential school, although it was not for lack of desire to create one. Under the direction of Jones and Ryerson, and others, a school was established at the Credit Mission.

It did not operate in the model of the residential school systems that we have come to critically analyze and condemn, as it did not remove students from their community and families. In simple terms the school at the Credit Mission, as we understand it from Professor Donald Smith’s extensive work, was more aligned with an overall cultural/linguistic/religious shift within the Credit Mission community.

Children at the Credit Mission were taught basic English reading, writing, arithmetic and etiquette. The teachings were reportedly both in Anishinaabe and English. It is difficult to separate the religious component from the educational aims of Jones and Ryerson, as both were fervent Methodist Ministers and missionaries. Certainly in Reverend Jones’ hopes and plans for the Mississaugas at the Credit River, religion and education were entwined.

Reverend Jones, with regards to securing a future for the Credit River Mississaugas in Upper Canada, believed that the Mississaugas must achieve equality in terms of civil and political rights “as soon as they are capable of understanding and exercising such rights.”

The establishment of a school at the Credit Mission was integral to this vision: the understanding of civil rights, land rights, and financial responsibility.

Peter urged the government and Chief Superintendent of Indian Affairs that the importance of establishing schools, both of learning and of industry, without delay, to assist with the education of the rising generation.

In early 1844, towards the end of Credit Mission village here in historic Mississauga, Reverend Jones advocated for the establishment of a manual labour school at the Credit Mission. For a myriad of reasons, the focus for this school shifted away from the Credit Mission to Munceytown.

By 1846, despite fundraising efforts abroad by Peter Jones, the plan to build a school at Munceytown had still not reached consensus.

The Muncey Institute (Mount Elgin Industrial School) did open in 1851. However by that time Reverend Jones, and other Indigenous leaders, found fault in their implementation and management and had begun to withdraw their support for the residential school concept.

Reverend Jones himself advocated for the establishment of residential schools “not as a means of erasing their separate identity, but rather as a tactic in the battle to survive.”

For Jones, it would seem that his own desires to establish formal residential schools did not align with what came to be. You have to wonder about Ryerson in the same lens – given that Jones and Ryerson maintained a lifelong friendship and correspondence.

Regardless, we have to acknowledge the role that Ryerson played in the implementation of residential schools, and the role that successive government officials and religious leaders, played in the ongoing perpetuation of the residential school model.

It was wrong. It was corrupt. It devastated families, communities and cultures. It killed children. It was government-endorsed institutional cultural genocide, and collectively we need to reconcile that within our pre-existing notions of Canadian history before we can find common paths forward.

There have been a great many articles published recently on both sides of the Ryerson debate. In my own evolving perspective, which is by no means at a full understanding of the issues at hand, I find myself balancing both perspectives. Ryerson, much like his peers, was both a builder and a colonizer.

His deeds help to build public education, while his concepts contributed to heartbreaking realities. He was flawed, just as the societal perspectives of race and culture were flawed in his time, and just as they are flawed today.

Our history is not static, and our connections and explorations of it continue to evolve. It can and should be a vital link in our sense of place, and pride in that place. But that needs to include everyone – from every walk, culture, faith, orientation and creed.

Ryerson is/was an easy target – the name, the statue. It is much harder to combat the ghosts of the ideals that preceded and succeeded Ryerson. The names of institutions that carry his name are being reviewed. Is it a critique of the individual, or of the entrenched political mindset that executed and perpetuated the plan? Does it matter? It is time to reflect on all sides of our narratives. The silence is broken. The statue is down. It likely should have been taken down long ago. It does not, and never did, represent the whole story.

Words and names carry power and meaning, and if they cause pain, confusion, disillusionment or impede healing, we should reconsider their usage. As for “Ryerson Road”, it has long since disappeared from our landscape, but the story, in pieces, remains. Yes, it can cause divisions. But hopefully it can also provide building blocks on the path toward reconciliation.

*You can find this article in Modern Mississauga as well:

https://www.modernmississauga.com/main/2021/6/9/exploring-mississauga-and-ryersons-road

Comments are closed.