During these days of COVID, and in observing Remembrance Day, I found myself re-reading some of our earlier submissions in this series relating to the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-20 and what happened locally for Armistice Day gatherings back then.

While the Spanish Flu arrived on Canadian shores in the spring on 1918, it was the deadly second wave in the fall of 1918 that brought the largest impacts, not only in terms of deaths, but also in closures, public health measures, and the prohibiting of public gatherings.

There were several factors that contributed to the rapid spread of the Spanish Flu in the fall of 1918: with the ongoing war, medical staff was scarce and hospitals were few; coal for heating purposes was in short supply, and the fall of 1918 was particularly wet and chilly; and returning soldiers brought the virus home with them.

At the end of September, local doctors were aware that the Spanish Flu was amongst them, but they were not completely aware of the virulent nature of the virus. News had been spreading from the United States, and only gradually did the medical community here respond with increasing alarm. In the absence of a central medical body coordinating a response, it fell to local medical officers of health to determine the course of action.

On October 5, 1918, the Toronto Star reported on the ordered closures of schools, churches, dance halls, theatres and all places of public assembly and recreation in Toronto. On October 11, conventions, meetings, funerals, and all public gatherings were prohibited:

Declared: All schools, seminaries, Sunday schools, dance halls, billiard and pool rooms, bowling alleys, theatres (music or concerts), halls – public or places or amusement, places for public gatherings and amusement are to be closed. All meetings or assemblies are prohibited, Public funerals prohibited.

Following suit, albeit a few weeks later, closures came to historic Mississauga (Toronto Township) towards the end of October.

The October 7 issue of the Toronto Star highlighted the poor conditions at the Orthopedic Military Hospital on Davisville Avenue and at the Long Branch Camp (located in Lakeview, in Mississauga), where colds and influenza were rampant. The October 8 issue of The Globe newspaper reported that hospitals “are taxed to capacity.”

As identified cases of the Spanish Flu rose exponentially on Toronto, vacant hotels became temporary hospitals, and beginning on October 12, 1918, the Toronto Star began to publish lists of the victims of the Spanish Flu.

As quickly as the second wave of the Spanish Flu arrived, it also waned. Between November 6 and November 14, 1918, active cases generally declined, and closure orders began to be lifted. However, it would not be the end of the story for the Spanish Flu.

The reopening in November, likely fueled in part by large Armistice Day gatherings, saw a spike in cases over the winter months and into the spring of 1919.

The Christmas break and school and church closures were extended in some communities. Although still viewed as a significant threat, this third wave of the virus was not as deadly as was the second. Other ebbs and flows followed in the fall of 1919 and the spring of 1920. When the virus disappeared on its own, it left broken communities and thousands of dead in its wake.

But back to the link to Remembrance: Armistice Day gatherings in 1918 saw people venturing out, congregating and celebrating in large numbers, in part due to the end of the war, and in part due to the perceived end of the Spanish Flu. Neither was correct. Following the Armistice Day gatherings, the newspapers reported that it was impossible to convince people to stay home. Despite a medical desire to maintain closures until December, people all over the province took to the streets to celebrate the Armistice. The medical community, in hindsight, viewed this sudden reopening as a mistake.

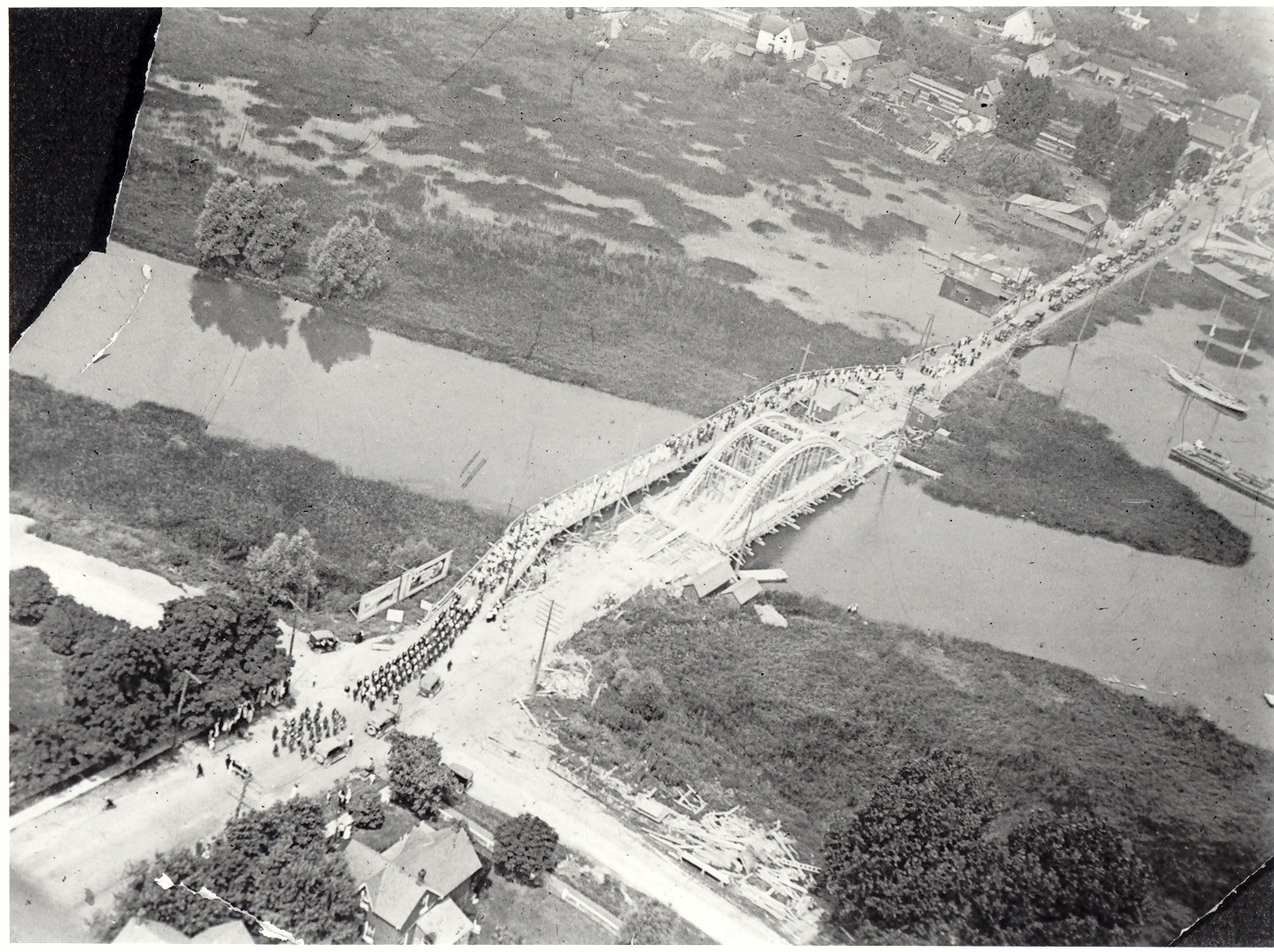

The First World War did not formally end until the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on June 28, 1919. Gatherings for returning soldiers were held in the summer months of 1919, including a Return Man’s Parade in Port Credit on August 4, 1919, followed by a large garden party at the Hobberlin Estate on Lakeshore Road. One wonders if this might have inadvertently led to an increase of Spanish Flu cases in the fall of 1919.

Of the hundreds of returning soldiers in historic Mississauga, two are known to have succumbed to the Spanish Flu here at home:

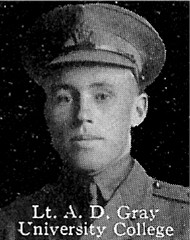

Lieutenant Angus Douglas Gray (1895-1918), was the youngest son on John Gray, president of the St. Lawrence Starch Company in Port Credit. He went overseas early in the war with the 4th Battlaion, and was wounded in action in October of 1916.

Returning to action in January of 1917, he received a Military Cross for his “conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty” at the battle of Vimy Ridge, where he continued to support the withdrawal and counter-attack of his battalion, even after suffering a wound to his forearm and the loss of one eye.

Lieutenant Gray returned home in the fall of 1918, possibly already suffering from the Spanish Flu. He died at home in Port Credit on October 25, 1918 of pneumonia.

Private Hubert Hutton McCaugherty (1898-1920) was the eldest son of David and Sarah McCaugherty. Hubert served with the 2nd Canadian Tank Battalion until he was discharged after the armistice, arriving home in time for Christmas of 1918. He is believed to have contracted the Spanish Flu while onboard a ship and he faced a long road for recovery. Sadly, he never did recover, and he passed away on June 23, 1920 from complications of influenza.

Comments are closed.