He glances at his watch. 1100 hours. It’s Saturday morning, April 30, 1949.

Today is a warm, early spring day at the Malton Airport and with a light breeze it seems a perfect day for flying.

The pilot prepares for a short routine test flight of the war surplus training aircraft`s fuel system.

It’s a poorly maintained piece of equipment with a recent history of water in the fuel system. The fuel lines were cleared with compressed air yesterday and flight test ready.

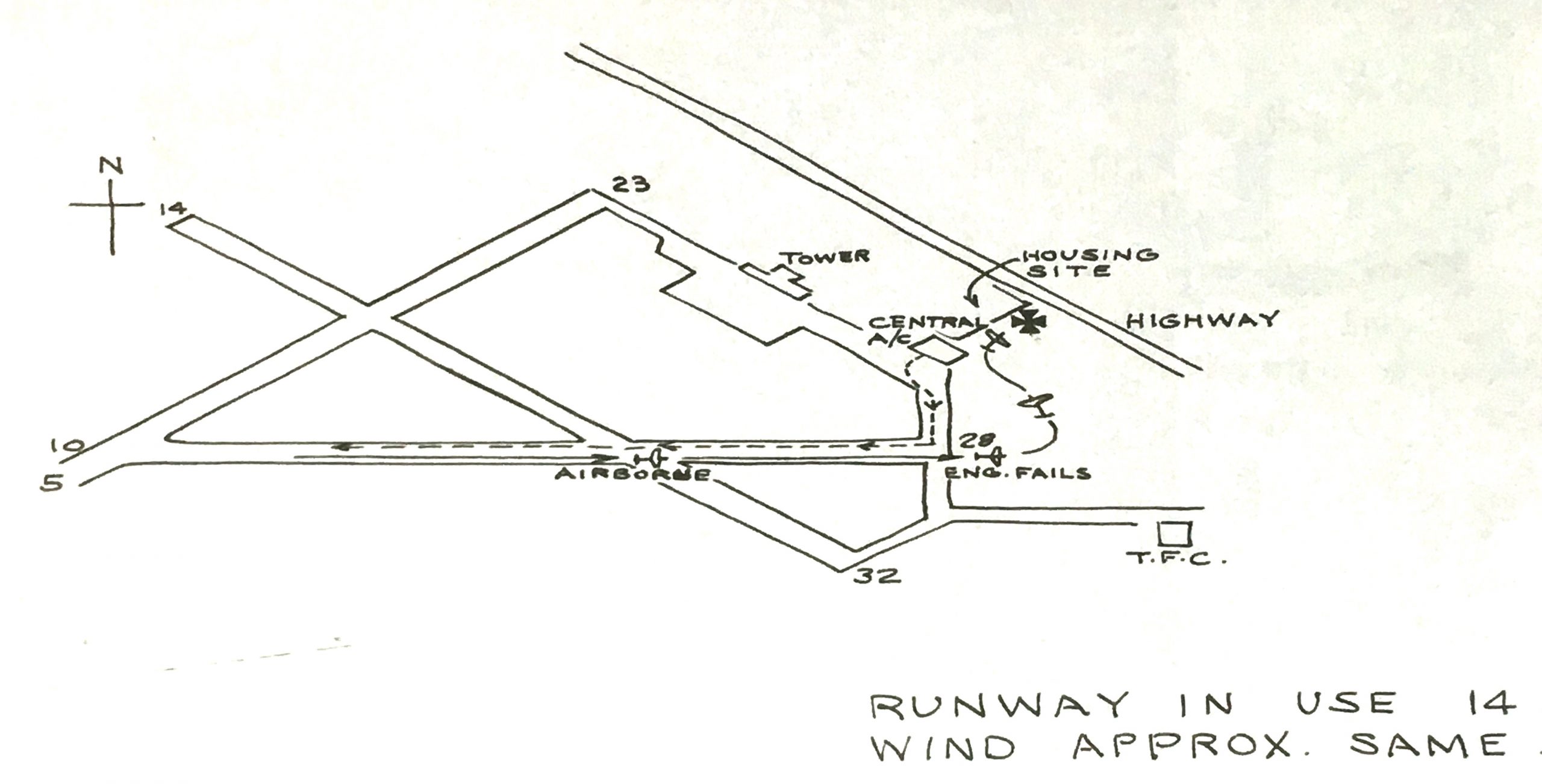

Runway 10 is chosen for the circuit flight and has plenty of room in case things do not go well.

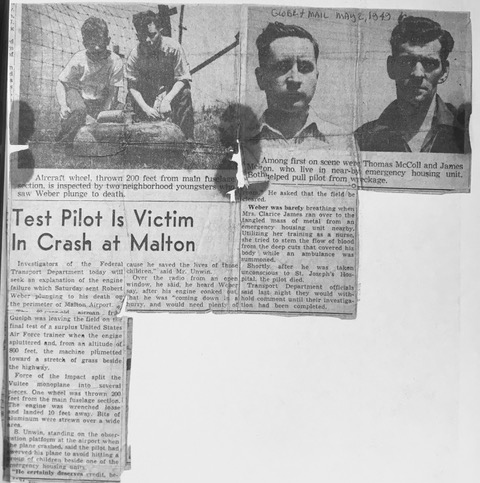

The pilot is twenty three year old Robert Weber, a World War Two Flying Officer veteran from Guelph and now a test pilot for Central Aircraft Ltd. at Malton Airport in Ontario, Canada.

A quick three minute circuit, “that’s it, stay within gliding distance” the company owner emphasizes.

They agree and the pilot continues his pre-flight check of the aircraft to ensure that nothing could obstruct cables or limit controls. This old trainer is in rough shape and extra care is given to the inspection.

Although marginally airworthy, nothing is found that would prevent a brief take-off and landing test.

Rolling the aircraft out of the hanger, it is positioned for start-up and some ground run-up testing.

Climbing into the forward compartment, the pilot adjusts all controls to appropriate settings and with the forward canopy open, the engine is started.

Spooling up with a characteristic series of exhaust spewing pops from the right side, the nine cylinder Pratt and Whitney radial engine settles into a smooth 800 rpm rumble.

All gauges are reading as they should.

Oil is 60°C with 60 pounds of pressure with a sustainable engine rpm of 2,000.

Reducing the engines speed and releasing the brake, the pilot taxies to the north end of Runway 10 and, setting the brake, again checks all gauges as he does another ground test of the motor.

There is no hint of any issues and the pilot prepares for takeoff.

Facing into a moderate easterly wind, runway 10 stretches out in front of the Vultee Valiant BT-13’s rumble.

At 2,000 rpm the pilot releases the brake.

With 450 horsepower released, the machine rushes forward into a clear sky.

Parts lacking a good fit shake at full throttle and the open canopy vibrates with a thunderous rattle as the craft is quickly airborne.

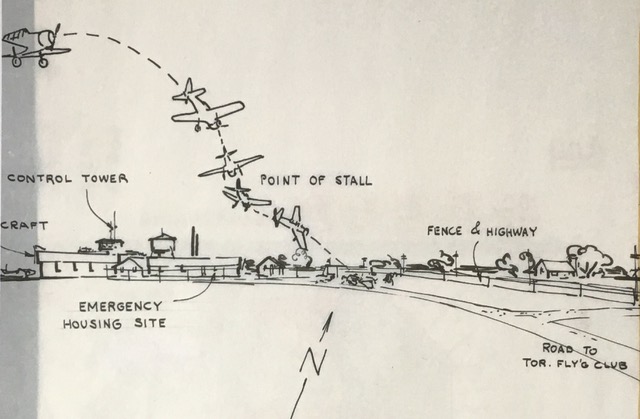

Seconds later, misfiring and then silence at 500 feet.

It catches and fails again. In rapid decent, the struggling pilot contacts the airport control tower.

“I’m coming down in a hurry. Clear the runway…need plenty of room.”

That’s what Bill Unwin hears through an open window as the pilot contacts Malton Airport’s control tower.

Standing on the airport observation platform, he watches the faultering aircraft struggle to make an emergency landing as its 450 horsepower radial engine gives way to silence.

At about 400 feet of altitude the 1942 war surplus trainer banks to the left in the hopes of making it to a runway or clear field.

Mrs. Wallace, a local resident, watches as the rapidly descending aircraft comes toward her home at the Malton Emergency Housing North Camp.

Adults and children in front of the units stand staring at him.

“We could see him in the cockpit,” she later told reporters, “he was looking right at us as he tried to head the plane away from the building.”

Leveled, with nose down to extend his glide path and hoping to prevent a fatal stall, the craft is quickly losing what little altitude it had.

Directly ahead is the Emergency Housing Camp located behind Central Airways Ltd. and a few hundred yards north of Airport Road.

A small field is between the Camp and the road.

The building is twenty feet high at its peak and the aircraft that is bearing down on it is slightly more than one hundred feet in the air.

Less than three hundred feet of distance, maybe four to five seconds, remains to the Camp in order to possibly clear the roof.

If he pulls up the aircraft will certainly stall, and he would have absolutely no control.

With no control a crash into the residences would be certain.

A nose down gliding strategy is the only hope to extend a motorless glide in this particular aircraft but clearing the buildings is quickly becoming a risky gamble as the heavy craft continues to rapidly descend.

Then it happens.

Wings and fuselage begin to shudder as the craft enters an “accelerated stall”.

No more lift.

With less than one hundred feet of altitude and a fading airspeed of eighty miles per hour, no successful climbs or turns are possible.

Below, to the pilot’s left, staring eyes of adults and children on the verandas meet his. Too close.

As the faces on the ground get closer, he makes a decision that will have only one outcome.

Pulling back slightly on the control stick and with a quick nudge of the tail rudder, the pilot intentionally causes a fully stalled right wing to dig into the grassy sod.

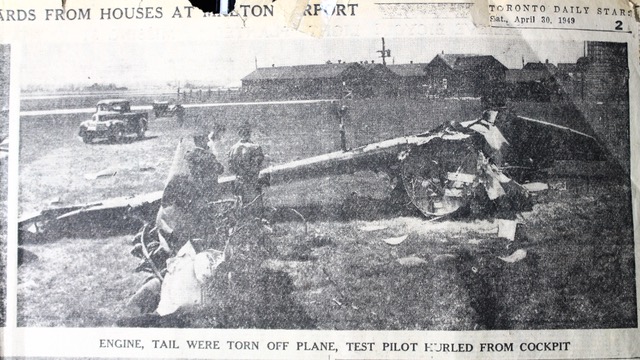

The aged aircraft cartwheels immediately and leaves a severed engine behind.

The left wing hits next and twists the fuselage onto its back and smashes the canopy and pilot to the ground.

Exploding aircraft parts scatter randomly as the canopy scraps along the grassy field beside Airport Road.

Within seconds the craft is completely demolished and lies smoldering three hundred feet away from the Emergency Housing Camp.

It is 1230 hours.

The crackle of a cooling engine resting thirty feet away breaks the ensuing silence.

The pilot ensured that he would clear the buildings without gliding over them.

It was this last second decision and manoeuvre, as the pilot fought to control his aircraft away from the homes in his path, that made it possible for the headline of the Saturday evening edition of the Toronto Daily Star to read “Hero Pilot Dies in Crash”

Mrs. Chalmer, a resident of the Housing Centre, was one of many to witness the crash.

“First thing I knew the nose seemed to drop and it headed right into the ground,” she later reported as she recounted the craft`s final moments. “It exploded just like a bomb, and then it bounced up into the air. Pieces of it flew all over the place. The ground seemed to shake under me.”

As the sirens of approaching airport emergency vehicles get louder, James Menton, Thomas McColl and Matthew Wallace run to the aircraft.

The impact of the crash has scattered engine, tail and wheels in various directions, throwing the pilot a few feet from the cockpit.

The three men lift the unconscious and battered pilot and move him away from the smoking wreckage.

Using handheld fire extinguishers, they manage to keep the more combustible broken pieces of aircraft from igniting.

Lloyd Marshall, aircraft mechanic with Central Aircraft Ltd., with local resident and nurse, Mrs. Clarice James, rush to the crash site and administer aid directly to the severely injured pilot.

Holding pressure against the neck artery, Mr. Marshall attempts to control the bleeding while Mrs. James attends to deep multiple cuts.

Refusing to accept the seeming hopelessness of the situation, they continue to apply medical aid until Dr. Ironstone arrives.

Mrs. James kneels holding the unconscious pilot as the Trans-Canada Airways crash truck arrives.

From the front of the torn and fragmented fuselage, smoke drifts over the rescuers.

The crash crew immediately disconnect the aircraft’s battery to prevent igniting the spill of fuel and oil.

One well-placed arc between wire and metal would likely result in an additional disaster.

A white blanket of soda and CO2 provided substantial insurance against this risk.

Surrounded by the smells of disturbed earth soaked with fuel and oil, a detached engine continued to crackle, alone, as it cooled seventeen feet away from the pilot.

Although the ambulance sped well ahead of its own cloud of field dust to the crash site, one observer said that it seemed “to take hours” for that ambulance from Saint Joseph’s Hospital in Toronto to arrive.

With the pilot secured in the ambulance, Mrs. James accompanied the pilot, Robert Weber, to the hospital. He died upon arrival.

Epilogue

This story is a factual dramatization of a real event that happened mid-day on April 30, 1949 at the Malton Airport.

All names and quotes are true and taken from newspaper reports at the time. The pilot was my father, and I was seven months old.

Any remaining facts are taken from a Department of Transport investigation into the crash.

They concluded the aircraft had a history of poor maintenance that a fuel flow problem occurred by the poor fit of the main fuel valve and/or an air lock in the line.

Pilot error was not considered a factor.

Remembering Flying Officer Robert Weber

Flying Officer Robert Weber, born on August 19, 1925, was the oldest of a family of seven children of Doctor George Harold and Marion Weber of Guelph, Ontario.

He was a member of the Kitchener-Waterloo Air Cadet Squadron and joined the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) as part of the British Commonwealth Flight Training Plan at the age of 17 ½ years of age.

He started his training at the No. 9 Elementary Flight Training School in St. Catharines, Ontario to train in Tiger Moth biplanes.

He then went on to the Service Flight Training School in Brantford, Ontario for multi-engine training.

He graduated as Pilot Officer at the age of 18 and was considered the youngest commissioned officer in the R.C.A.F.

Following this, he did post graduate training and was promoted to Flying Officer on his 19th birthday in 1943.

He was also the youngest commissioned officer in Canada when he was placed on an overseas draft.

He never reached that goal and was based in Charlottetown, P.E.I. in the coastal command and flew Anson Mark V’s at the Air Navigational School in Charlottetown.

In 1944 he met “a Charlottetown girl” – 17 year old Annie Margaret McInnis. In August of 1945 they were married in Charlottetown.

Following the war, they moved to various locales as Robert (sometimes called Bob or Rusty) flew for Maritime Central Airways, Sturgeon Air Services and Rimouski Airlines, and served with the New Brunswick 5th Armored Regiment (8th Hussars) before moving to Malton with Margaret and a seven month old son in March of 1949.

Editor’s note: Pilot Officer Robert Weber’s seven-month old son from 1949 is the author of this article.

Comments are closed.