2020 marks the 75th Anniversary of the end of the Second World War. But making sense of dates can sometimes be confusing. At times, the Second World War offers a complicated narrative. But before I delve into the end of the Second World War and some of our connections, allow me a moment to step back and look at Canada’s traditions of remembrance for our fallen soldiers.

When looking back on the timeline of the First World War, most of us can readily connect to the date of November 11, 1918 as the end of that conflict (November 11, 1918 marked the armistice, or ceasefire, that brought the actual fighting to a close. The Treaty of Versailles – or officially The Treaty of Peace between the Allied and Associated Powers and Germany – formally ended the war and was signed on June 28, 1919). The Armistice of November 11 (or the Armistice of Compiegne), which came into effect at 11 am on November 11, marked the end of hostilities and the silencing of guns in the First World War. The day was celebrated throughout Western Europe, the United States, and Canada. Today we all connect the observance of Remembrance Day with November 11. But that was not always the case.

Before Remembrance Day as we knew came to be, commemoration for the fallen had its roots in what was known as Decoration Day, which was first observed on June 2, 1890 in remembrance of the Battle of Ridgeway during the Fenian Raids in 1866. Decoration Day continued to be observed, although it declined somewhat in terms of public participation, throughout the First World War. Fallen soldiers from the First World War were initially honoured on Decoration Day.

According to the Canadian War Museum, in April of 1919, Isaac Pedlow, Member of Parliament for South Renfrew, introduced a motion in the House of Commons to create an annual “Armistice Day” on the second Monday of November. Parliament agreed that there should be a special day, but did not agree on the day it should be held. Some argued that it should occur on the date of the armistice itself, regardless of the day of the week; others thought it should remain tied to Decoration Day. On November 6 an appeal was made by King George V to the British Empire to urge that the year-old Armistice be marked by the suspension of all ordinary activities and the observance of two minutes of silence at precisely 11 am on November 11. Canada adopted this practice, at least for 1919 and again in 1920, but it did not conclusively settle the date question. Some communities continued to honour Decoration Day, with dates ranging from mid-May to mid-August, while other communities marked Armistice Day. In the early years, there was considerable variety across Canada.

In 1921 Member of Parliament H.M. Mowat, of Toronto again brought a proposal before the House of Commons for a special annual Armistice Day to be held on the Monday of the week in which November 11 fell. This was to be joined with Thanksgiving Day, until then a floating holiday held at the government’s discretion. Parliament passed this proposal as the Armistice Day Act in May of 1921, thereby creating a single new holiday on a long weekend. However this proved unpopular with veterans and the public at large.

Armistice Day and Thanksgiving remained linked for the next decade. Held every year on the Monday before November 11, Thanksgiving was celebrated with special dinners at home and sports and other activities outside. In contrast, even though it was not an official holiday, November 11 saw large gatherings at local cenotaphs and war memorials. This “compromise” could not last. In 1925 the newly formed Royal Canadian Legion passed a resolution stating that Armistice Day should be held only on November 11 and led a campaign to have this enacted by Parliament.

On March 18, 1931, A.W. Neil, Member of Parliament for Comox-Alberni in British Columbia, introduced a motion in the House of Commons to have Armistice Day observed on November 11 and “on no other date”. C.W. Dickie of Nanaimo, also speaking on behalf of veterans, moved an amendment changing the name from “Armistice” to “Remembrance” Day. Parliament quickly adopted these resolutions as an Act to Amend the Armistice Day Act. Canada held its first Remembrance Day on November 11, 1931.

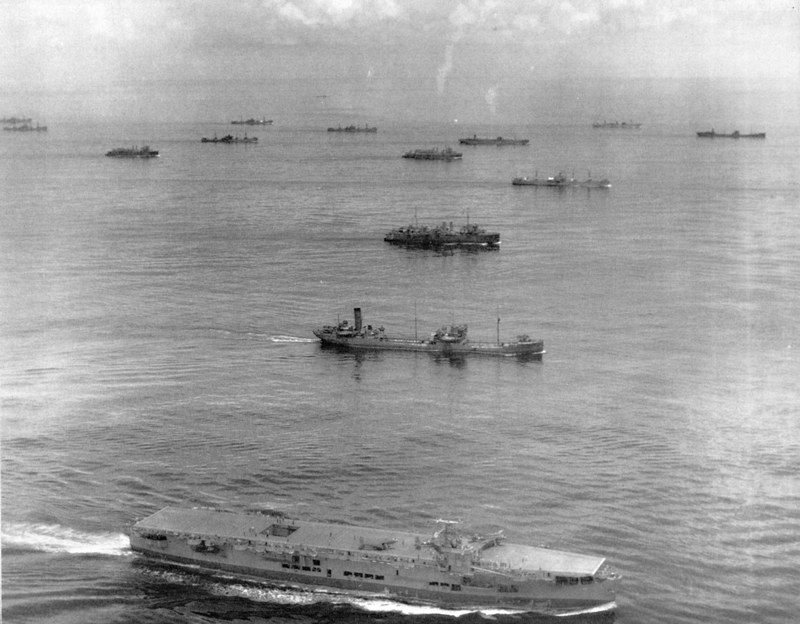

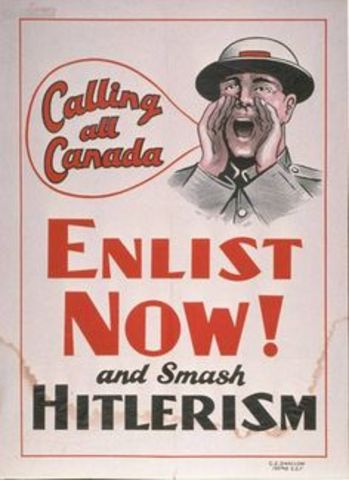

A few short years later, the world was once again at war. From 1939 to 1945, the Second World War raged across the globe. As with other wars, moments within the larger conflict began to be marked at home. Canadian soldiers found themselves engaged in battle on multiple fronts throughout the war, with news of casualties reaching those at home and covered in the newspapers of the day. Names like Dieppe, the Battle of the Atlantic, Sicily, Ortona, Liri Valley, Normandy, Juno Beach, D-Day, Caen, Scheldt, the Rhineland Campaign, Hong Kong, V-E Day and V-J Day, amongst many others, became familiar, just as the mounting losses were mourned.

Throughout the Second World War, and after, November 11 was the official day to remember those that served and those that fell. In the decades that followed, dates that marked the end of hostilities in the Second World War have become obscure and most often pass without formal recognition, with commemoration in terms of public acknowledgement in succeeding generations most often being connected to the November 11 date.

As mentioned at the beginning of this article, 2020 marks the 75th Anniversary of the end of the Second World War – although a specific date requires a bit of explanation. May 2, 1945 marked the end of the war in Italy and the Mediterranean. May 8, 1945 is known as Victory in Europe (or V-E) day, and marks the German surrender (Russia honours May 9 as the official date of the signing of the German Instrument of Surrender). But the war was not truly over. With the cessation of hostilities in Europe, attention turned to Japan and the ongoing Battle of the Pacific. Following the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9, 1945, Japan announced its unconditional surrender on August 14, 1945 – which was announced in the United States and Canada on August 15, 1945. The formal Japanese surrender was signed on September 2, 1945. In Canada, Victory Over Japan Day (V-J Day), and the end of the Second World War, is commemorated on August 15. In the United States, the date of commemoration is September 2. So, in short, Canada recognizes August 15 as the end of the Second World War, but in other countries other dates hold significance as well.

In all, some 1.1 million Canadian men and women served in the Canadian Army, Royal Canadian Navy, Royal Canadian Air Force, Canadian Women’s Army Corps, the Red Cross, and in other forces across the Commonwealth, with approximately 43,000 killed and another 55,000 wounded. Approximately 1 out of 25 enlisted Canadian service members did not return home. Among those fallen were 89 soldiers, identified to date, from historic Mississauga. The average age of our fallen was 24 years old. We remember their brave service.

Research into the fallen of the Second World War from historic Mississauga continues, and we look forward to sharing stories and biographies of our fallen in the months ahead. For more on the Second World War, we invite you to join us for our Ask A Historian program on Heritage Mississauga’s YouTube channel at 4 pm on August 27 as we explore more about Mississauga’s connections and Second World War.

NOTE: This story was previously published as part of the Way Back Wednesday series in Modern Mississauga by Heritage Mississauga.

It can be found on their website here: https://www.modernmississauga.com/main/2020/8/26/way-back-wednesday-a-question-of-dates-75th-anniversary-of-the-end-of-the-second-world-war

Comments are closed.