Vimy is a name that rings proudly through Canadian history. Even for those who may not know the story of what, when and why, most connect the word Vimy with remembrance and sacrifice, even 104 years later.

The Battle of Vimy Ridge took place from April 9 to 12, 1917, as part of the Arras Offensive in the First World War. For the young nation of Canada, it became a symbol of Canadian nationalism, although strategically the battle had little impact on the course of the overall war.

The Battle of Vimy Ridge marked the first time that all four divisions of the Canadian Corps fought together, and the victory at Vimy was the largest territorial advance of any Allied force to that point in the war. The cost was high. Some 100,000 Canadian soldiers served at Vimy, with 3,598 killed and 7,004 wounded.

As part of the allied offensive in the spring of 1917, the Canadians Corps were assigned the German-held strategic high ground at Vimy, coordinated with British and French attacks elsewhere along the German front. Early in the war, both British and French attempts to take the ridge had failed disastrously.

The Canadian Corps made the most of the months leading up to the offensive with extensive planning. The area around Vimy became a busy, militarized, industrial zone, with thousands of soldiers rehearsing the coming attack on the ridge, and thousands more working on infrastructure supports – such as building roads, railway tracks, tunnels and trenches. Much of the work and the movement of troops was done in the darkness of night to avoid being seen by the enemy.

Many of the soldiers were sheltered to the west in towns and tented camps, while thousands of others were housed underground in old chalk mines, or souterrains. Food supplies, water distribution, and communications had to be methodically planned. Even a saw mill was established to meet the need for lumber for construction projects to support the growing army.

In the weeks leading up to the battle, Canadian soldiers raided German positions to gather intelligence, while aerial reconnaissance scouted enemy trenches and machine gun placements.

Underground tunnels leading towards the German lines called “subways” were built, designed to bring many of the attacking Canadian soldiers out safely, closer to the German lines without having to cross wide areas of “no man’s land”. Casualty clearing stations were also established.

A large scale map of the ridge was created for training, and the attack was rehearsed over and over again. Soldiers were given detailed information on German positions and terrain.

Command on the battlefield was spread amongst the troops, so that even with the loss of officers, the attack could continue. Soldiers and non-commissioned officers were encouraged to think for themselves.

New artillery tactics were also employed at Vimy, including the execution of a “creeping barrage” – sustained artillery fire in front of advancing troops, aimed to protect their advance and to force German troops to seek shelter in their bunkers.

More than 980 heavy artillery pieces were employed at Vimy. In the week leading up to the attack on April 9, more than a million artillery shells poured down on German positions. The artillery bombardment continued until the evening of April 8. At 5:30 am on April 9 – Easter Monday – the attack began, behind the curtain of the “creeping barrage”.

Some have called this wave of the Canadian advance the “Vimy Glide” – attacking soldiers were expected to advance 100 yards every three minutes, to keep time with the artillery fire, but not to outpace it.

Every three minutes, the artillery would aim a little higher, advancing the shellfire forward in front of the attacking troops. The exploding shells sent plumes of dirt and shrapnel into the air with each impact, leaving massive craters behind.

The plan for the advancing soldiers was fairly simple: move forward, never stop, never race ahead. Falling too far behind would mean possible exposure to German machine guns, while getting too far ahead would put them in danger of their own artillery.

By all accounts, the attack plan was executed perfectly, and with stunning speed. Within a few hours, the main part of the ridge was in Canadian hands, including the strategic points of Hill 135 and the village of Thelus.

The entrenched German position on Hill 145 was captured on April 10, and finally, on April 12, Hill 120 (also referred to as “The Pimple”) fell to the Canadian Corps. The German army withdrew, and the Battle of Vimy Ridge was over.

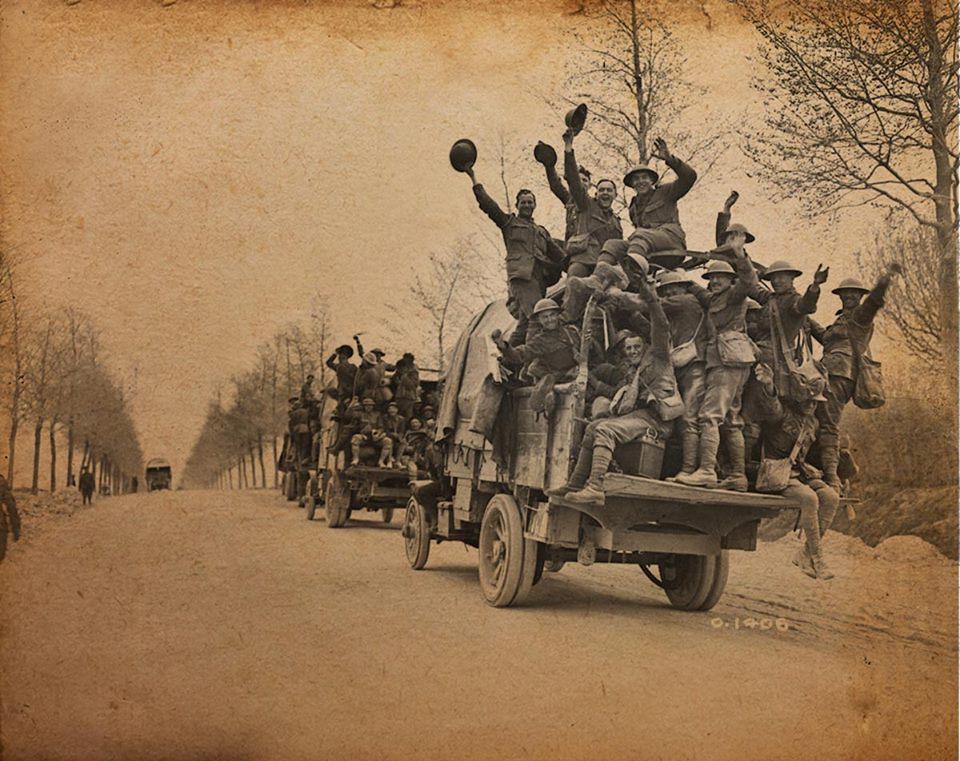

Newspapers in Canada hailed the success of the Canadian army at Vimy, and it was seen as a unifying symbol at home – Canadians from across the country fighting together and achieving a great military success on the world stage.

Although most of the other parts of the larger Arras Offensive failed, in Canada the Battle of Vimy Ridge stood as a point of national pride – while also connecting those at home with a sense of connection through loss.

Canadian soldiers would continue to serve, and distinguish themselves, throughout the remainder of the war, and while major successes for the Canadian Corps were seen later at Hill 70 at Lens, Amiens and Cambrai, Vimy stood out in the public consciousness at home.

Amongst those who served at Vimy there are known to be 7 killed and 11 wounded from historic Mississauga.

Those who fell at Vimy include Private Dennis Ainger of Erindale, Sergeant Thomas Cartwright of Erindale, Private Joseph Clarke of Streetsville, Private William Kidd of Clarkson, Private Eli Rossiter of Clarkson, Private Jack Young of Clarkson, and Private James Fawcett of Streetsville.

Captain Reverend George Petrie Duncan of Port Credit was the chaplain for the 2nd Canadian Brigade at Vimy. He later wrote a report on the battle, and in it, after reviewing the battlefield, he wrote “…evidence of the bravery of our men could be seen all around. It has been a privilege to do some little things in the great advance.”

Comments are closed.