Some time ago, local historian, author and storyteller Alan Skeoch penned an article remembering the late Lorne Joyce and recalling the heady days of rum-running in Port Credit. Lorne, himself an avid storyteller, author and marine historian, often regaled members of local historical societies with tales from life on the Great Lakes. I fondly recall hearing Lorne, with a twinkle in his eye, speak about rum-running.

Some time ago I jotted down some of the things he spoke about. Alan’s article also connected with Lorne’s remembrances, and wonderfully recalled Lorne’s memories in his own voice. So, to Alan and Lorne: thank you for the stories, and for the inspiration for this short article. I can still hear Lorne’s voice telling the tales.

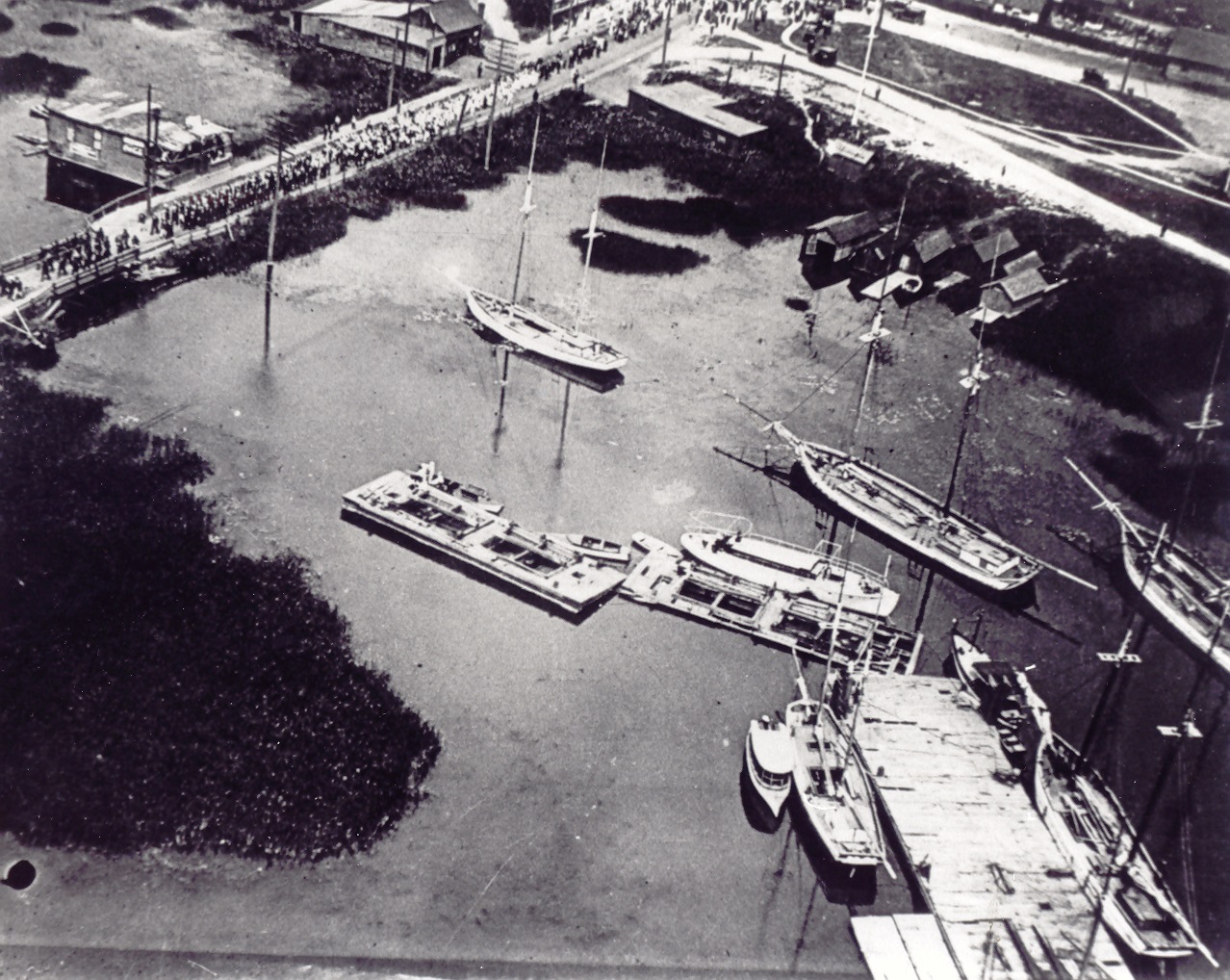

Rum-running was a fascinating, if short-lived, part of Port Credit’s story. It reached its heyday during prohibition and temperance in the 1920s. Many fishing vessels operating out of the quiet port at the Credit doubled as cargo vessels in the illegal trade of alcohol.

There was a complex network of “eyes” that helped to deflect attention and outsmart authorities – including spotters on shore, at the fish shanties, the dock, and the railway station that would ensure the illegal cargo could be offloaded, stored and transported.

Port Credit was ideally situated to be part of the rum-running industry. Located between the urban markets of Hamilton and Toronto, it had a harbour with a large number of fishing vessels, close proximity of the railway to the harbour and the shoreline, and a low number of law enforcement personnel.

For a time, the local police representation consisted of one paid officer, who could be redirected by way of a false alarm to allow the rum-runners to either load or unload their cargo without police interference.

But why were there rum-runners at all?

Laws were enacted that prohibited the sale of intoxicating liquors, and some people – okay, a lot of people – disagreed. Rum-running was part of the industry to meet (and profit from) consumer demand during prohibition.

Prohibition in Canada came about through a long process of advocating for temperance and the closing of bars and taverns – which were seen as dens of vice and misery. Temperance societies believed that alcohol affected society’s moral, economic and religious prosperity.

In Canada the Scott Act of 1878 gave authority to individual municipalities to opt to become “dry” – that is to regulate and eliminate the sale of alcohol. National prohibition (seen largely as a wartime measure) came into being during the First World War.

Prohibition in Ontario was in effect from 1916 until 1927 under the Ontario Temperance Act, which banned alcohol sales (and public consumption). Banning alcohol in Canada was challenging in that while the Province could control sales and consumption, it could not legislate the making and trading of alcohol. And thirsty customers provided a ready clientele for those willing to skirt the rules.

In the United States the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which banned the manufacture, transportation and sale of alcohol, also brought in the Prohibition era in the US in 1920 with the passage of the Volstead Act.

Like the Canadian experiment, Prohibition was difficult to enforce, let alone monitor. Hungry (or thirsty) customers were catered to by bootleggers, who in turn brought in an era of organized crime and speakeasies. Rum-runners were part of the mix, supplying alcohol to bootleggers, who, as the middle-men, brought alcohol to a willing public. There was money to be made, and lots of it.

Rum-running on Lake Ontario played a significant, if short-lived, role in the underground trade and transport of alcohol. In the US, the manufacture, sale, and transportation of alcohol was prohibited, whereas in Canada alcohol could be legally produced, but not sold domestically.

A shipment of alcohol would be sent by train to Port Credit, and with the local police constable sufficiently distracted, the alcohol would be quickly loaded onto a waiting boat, where it would be sailed to its drop-off point, usually connecting to a bootlegger at another Canadian or American locale on Lake Ontario.

On occasion, if there was need to hide their cargo from authorities, cases of alcohol would be tied in sacks and dropped overboard with a long rope, only to be retrieved later when the coast was clear.

Although there are references to local rum-runners distributing to American ports-of-call in the dead of night, most of the alcohol transported out of Port Credit seems to have been destined for Canadian bootleggers and for local markets.

The first part of rum-running was legal at the time – alcohol could be purchased from distillers, but just not sold to Canadians. Distillers did not require proof of destination, and many of the sailors carried fake export documents showing that their cargo was destined for the French possessions of St. Pierre and Miquelon.

Rum-running out of Port Credit, and other Lake Ontario ports, lasted as long as prohibition was in place, which ended in 1927 in Ontario and in 1933 in the US, bringing the lucrative trade to an end.

Comments are closed.