This week’s article continues with our nautical theme and the evolution of the harbour at Port Credit. Last week’s article looked at the development of the harbour in the 1960s and the arrival of Canada Steamship Lines. One hundred years earlier, a different industry called the harbour at Port Credit home.

It has been said that Toronto was built on Dundas Shale. A careful look at the foundations of buildings erected in Toronto (and in Port Credit) prior to 1910 often reveals stone foundations. In an age before the ready availability of concrete, a constant supply of building stone was essential. Beginning in the 1840s and lasting until just after the First World War, the Lake Ontario waterfront between the Credit River and Burlington Bay was busy with those engaged in mining the shallow waters for shale and loading the stone onto small sail-driven vessels known as stonehookers.

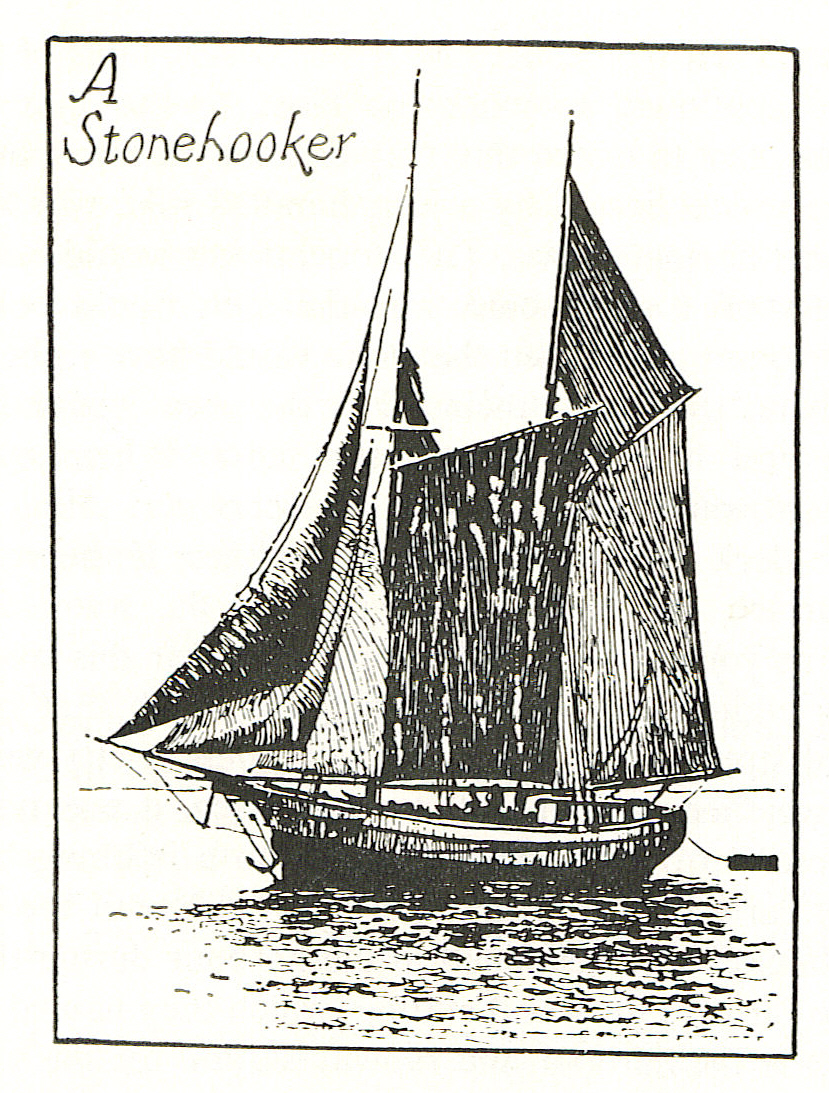

In order to mine Lake Ontario for stone, a new marine industry, unique in Canadian history, was developed. The stonehooker was a small vessel, usually between twenty to one hundred tons in burden. Schooner-rigged with minimal draft, the typical stonehooker could sail fast in light winds.

Port Credit, Oakville and Bronte became the centre of the industry. On the backs of the stonehooking trade, and the sailors who plied the waters and harvesting the stone, Port Credit grew rapidly between the 1850s and 1880s.

Many stonehooking vessels were built at the shipyards in Port Credit, and many more called the port their home. There were dozens of vessels that worked the stonehooing trade, including the Ann Brown, Ariadne, Arthur Hannah, Catherine Hays, Defiance, George Dow, Hunter, Lithophone, Lillian, Lone Star, Mabelle, Madeline, Mary Ann, Mary E. Ferguson, Maude S., Newsboy, Olympia, Raleigh, Rapid City, and Reindeer, amongst many others.

Other stonehookers who sailed out of Port Credit were wrecked or lost on Lake Ontario, along with the sailors who sailed them. These included the Anna Belchambers, Augusta, Barque Swallow, Coronet, Jessie Drummond, Morning Star, P.E. Young, Pinta, Sampson and White Wings.

There are many stories of stonehookers lost in storms, and of sailors who never returned home, their resting place somewhere under the deep, cold waters of Lake Ontario. Schooner Days by C.H.J. Snider, along with several articles and book excerpts by the late Port Credit historian Lorne Joyce recall the heyday of the stonehooking trade.

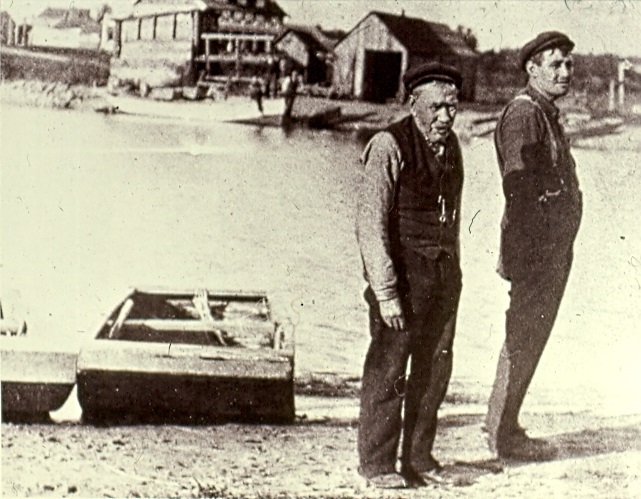

In order to harvest shale from shallow waters, a stonehooker would anchor close to the shore, usually in anywhere from six to twelve feet of water. Stonehookers typically carried a crew of two or three. The crew would then pry slabs of shale from the lake bottom using long rakes (“hooks”). The stone, when harvested, would be loaded onto a small scow. When filled, the scows would be poled to the waiting schooner where the stone would be offloaded onto the stonehooker’s deck. Stonehookers such as the Lillian and the Newsboy could carry thirty tons of stone on deck. The toise was the standard measure for stone. Piled in rectangles three feet high, six feet wide, and twelve feet long, weighing 10 tons, a toise would bring the stonehooking crew, depending upon the year and the demand, between $3.00 and $5.00. Three trips a week at two toise a trip was considered an excellent output for an average two-man crew.

Many stonehookers worked as close as possible to the actual shore. This allowed workers to wade in the water, prying loose the shale with crowbars. Many of the waiting barges were equipped with hoists and A-frames that assisted in loading shale onto the barge. Much of the stone was taken to Toronto where it was piled on Queen’s Wharf at the foot of Bathurst Street. From there, it was removed to construction sites throughout the City, usually to be employed in forming the foundations for many of Toronto’s stone and brick buildings.

Stonehooking was backbreaking work, and could be dangerous as the small stonehookers often succumbed to storms on the lake, with more than a few boats and sailors being lost in the waters of Lake Ontario. The names of Port Credit’s stonehooking families ring through the years as well, including Block, Blower, Cavan (Caven), Hare, Harrison, Lynd, Miller, Naish, Newman and Peer, amongst many others – lives that were all connected to the ebbs and flows, harvests and hardships, of the lake. Many of their former houses still stand within the community.

Unfortunately the mining of shale deposits close to shore robbed the shoreline of natural protection, and erosion became an increasing issue. By the late 19th Century, the Three Rod Law was passed that did not allow the harvesting of stone within about 50 feet of the shoreline, but this did not solve the problem. The stonehooking trade declined as available shale deposits in shallow waters were depleted and as concrete became a more popular building material after 1910. Some of the old, weather-beaten schooners were sold and converted to barges until the last of their usefulness was spent, then to be broken up, scuttled, used as breakwaters, docks, or even burned for amusement at Sunnyside Amusement Park in Toronto. The last of the active stonehookers, the Lillian, was sold in 1929, bringing the era of the stonehookers to an end.

One modern link to the era of the stonehookers on our modern landscape is Saddington Park in Port Credit. The park was created through landfill in the 1960s to protect the vulnerable shoreline from further erosion as the shale had been removed decades earlier.

NOTE: This story was previously published as part of the Way Back Wednesday series in Modern Mississauga by Heritage Mississauga.

It can be found on their website here: https://www.modernmississauga.com/main/2020/9/23/the-history-of-stonehookers-in-mississauga

Comments are closed.