June marks National Indigenous History Month, with a particular date focus on June 21 and National Indigenous Peoples Day, encouraging Canadians to celebrate and learn more about the cultural identity and diversity of First Nations, Métis and Inuit peoples. In connecting with our ongoing “medical theme” with the Way Back Wednesday article series during these days of COVID-19, this week we will look at the first licensed Indigenous Doctor in Canada who was the son of a Mississauga Chief of the Credit River Mississaugas.

Peter Edmund Jones was the third child of Mississauga Chief Reverend Peter Jones and Eliza Field. His father, Reverend Jones, had championed the cause of the Mississaugas of the Credit River for decades prior to his assignment, on behalf of the Methodist Church, to the Muncey Mission, near London, in 1841. Peter Edmund was born here in 1843. His Ojibwa name was Kahkewaquonaby, the same as his father. Peter Edmund spent much of his early life at the Muncey Mission, and in 1851 moved, with his family, to their new home near Brantford, dubbed “Echo Villa”.

Peter Edmund Jones was the third child of Mississauga Chief Reverend Peter Jones and Eliza Field. His father, Reverend Jones, had championed the cause of the Mississaugas of the Credit River for decades prior to his assignment, on behalf of the Methodist Church, to the Muncey Mission, near London, in 1841. Peter Edmund was born here in 1843. His Ojibwa name was Kahkewaquonaby, the same as his father. Peter Edmund spent much of his early life at the Muncey Mission, and in 1851 moved, with his family, to their new home near Brantford, dubbed “Echo Villa”.

Although Peter Edmund would spend much of his life devoted to the Mississaugas, his biography notes that a cultural gulf separated Peter Edmund from many of the Mississaugas as he was raised and educated in a largely non-Indigenous world. His education included, in his early years, an English-styled governess and attending the Brantford Grammar School. He later attended medical school at the University of Toronto and Queen’s College in Kingston. He received his medical license in 1866, and is recognized to be the first Indigenous person in Canada to obtain a medical degree.

Peter Edmund’s father, Reverend Peter Jones, passed away when he was 12 years old, and although he was viewed as only being ¼ Mississauga, Peter Edmund identified himself as Indigenous and connected to this part of his heritage. He also sought to follow his father in working with the Mississaugas.

After attaining his medical degree, Peter Edmund settled in Hagersville, adjacent to the New Credit Reserve, and established his practice. He was elected as Chief of the Mississaugas from 1874 to 1877 and from 1880 to 1886. Much in the spirit of his father, Peter Edmund worked to attain the civil rights for Indigenous peoples in Canada enjoyed by other British subjects, without surrendering their own legal status and cultural identities. Although he did not achieve all of his goals, he did aid in laying the groundwork for future efforts. Peter Edmund took part of the consultation for the 1885 Electoral Franchise Act, which gave “Indian-status” men in limited voting rights without losing their status – the first of its kind in Canada, although still a long way from full enfranchisement.

From 1887 to 1896 he was appointed as the Indian Agent to the Mississaugas at New Credit. Throughout his time as both Chief and Indian Agent, Peter Edmund continued his medical practice, and was a much respected doctor amongst the Mississaugas and the Six Nations Haudenosaunee. Peter Edmund sought to alleviate diseases on reserves through vaccination programs, advocated for cleaner sanitary and waste disposal practices, and for clean, potable water on reserves.

In addition to his primary tasks, Peter Edmund also published his own newspaper, the Indian, for one year, producing 24 issues from December 1885 to December 1886. It was the first Canadian publication for Indigenous people produced by an Indigenous person. He was also a collector of Indigenous artifacts, and, through his mother, saved many of his esteemed father’s papers, books and regalia.

Like his father, Jones lived across the cultural gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. To many, Peter Edmund was a puzzle, a man who walked with feet firmly planted in two worlds, yet never truly comfortable or welcomed in either. He married an English widow, Charlotte Dixon. While the couple did not have children of their own, Peter Edmund played an important role in the lives of her children from her first marriage.

Peter Edmund had eclectic interests that ranged from being regarded as an avid chess player to an amateur Victorian-era amateur archaeologist and taxidermist, aside from his contributions to medical science and health care amongst Indigenous peoples. Unlike most University-educated Indigenous peoples, Peter Edmund refused to give up his status and continued to identify himself as Indigenous, and took great pride is his own heritage and that of the Mississaugas.

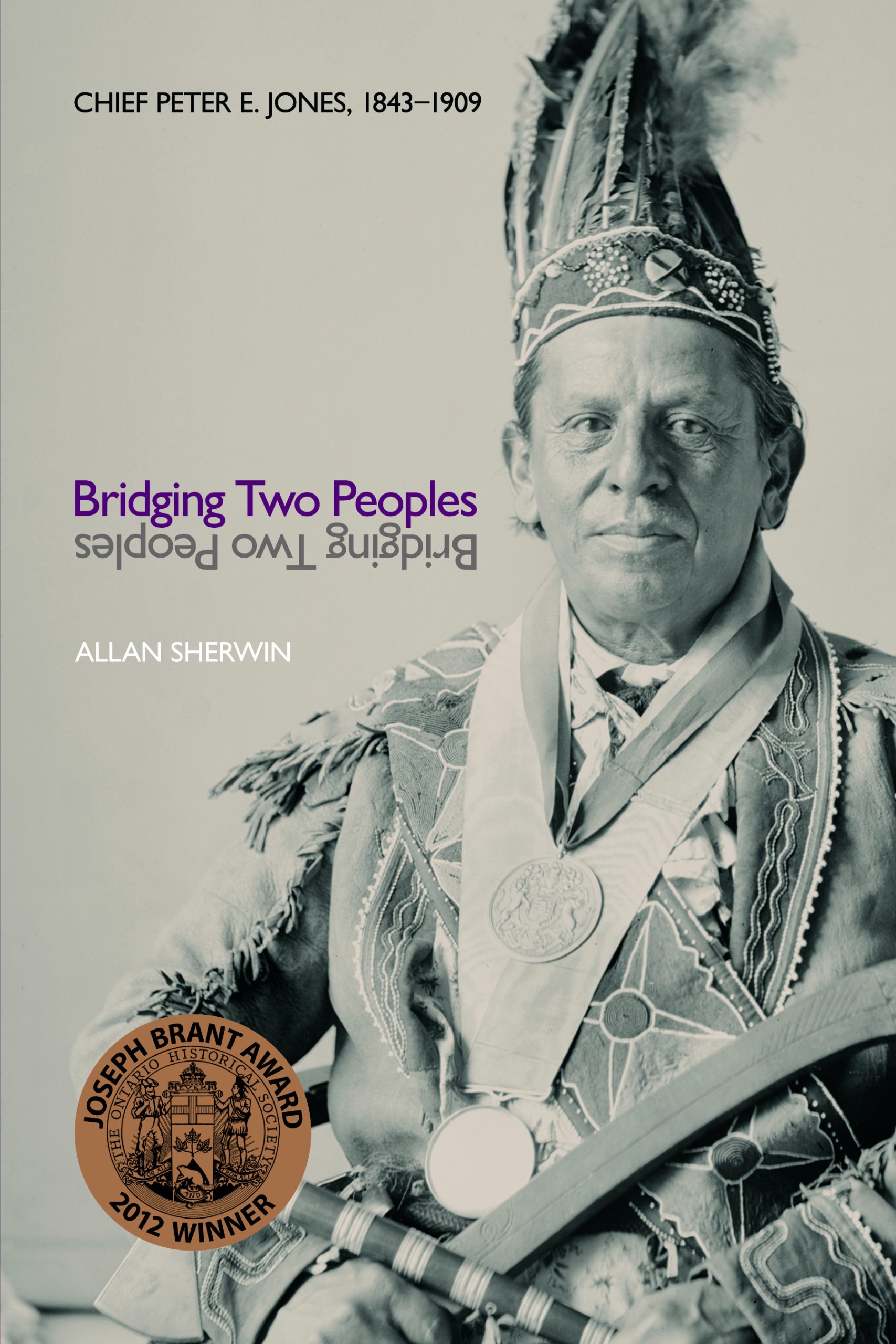

For more information on the fascinating life and times of Doctor Peter Edmund Jones (1843-1909), I highly recommend the biography Bridging Two Peoples by Allan Sherwin (2012). You can also read more through the Dictionary of Canadian Biography online and in this article published in the Queen’s Journal: www.queensjournal.ca/story/2016-09-30/features/the-duality-of-peter-e-jones/

NOTE: This story was previously published as part of the Way Back Wednesday series in Modern Mississauga by Heritage Mississauga.

It can be found on their website here: https://www.modernmississauga.com/main/2020/6/17/the-history-of-mississaugas-doctor-peter-edmund-jones

Comments are closed.