“I Put my Spark in There, My Own Way”: The Artistic Life and Times Angelo Belluz

“I Put my Spark in There, My Own Way”: The Artistic Life and Times Angelo Belluz

By: Justine Lyn

Artist Angelo Belluz was born into a farming family in the Azzano Decimo, Pordenone countryside in Italy in 1924. In 1947, he married dressmaker Anna Delbel and just two years later, he made the biggest trip of his life.

He immigrated all the way to Canada, settling in Port Credit upon arrival. He came at first by himself to get settled before his wife joined him. Those days in the very beginning were very difficult and at times, he questioned whether he had made the right decision.

In the beginning, there were very few Italians in Toronto Township (now Mississauga). The feeling was isolating until he began making a few friends. “There was only a couple [Italian] families. [One day], there was a festival in Port Credit. So, walking along, I saw one man come toward me. He said, “Are you Italian?” “Yes I am.” He was speaking my dialect, kind of. I was so happy to hear that. He was here way before I was, so he knew the area around. So we started to get together,” Angelo recalled.

“You know, as an immigrant, sometimes you’ve got to stick together because you’ve got no other place to go. You cannot speak the language. The Canadians here they don’t understand it. They kind of looked at us sideways the same way we looked at a dog sideways. […] A few years after, five or six years after, then from Italy, [people came from] everywhere actually [just] trying to survive. But it was good here for only one reason, to be honest with you, for the money, that was all for us,” explained Angelo.

In 1950, Angelo began to work at the Cooksville Brickyard, then known as Laprairie Brick. He remembered this early time saying, “See, the jobs were very scarce at the time. I was thinking to myself, if I go work in construction, I’ll get 6 three or four months off [during the winter]. So, working at the brickyard, they work all year ’round. Low pay, but in the end you make more than the others. Everyday you go to the same place. So it was better off to stay put, for me to stay there [and work at the brickyard].”

At the time, Belluz explains that, “Cooksville was just a small town. I remember, I lived in Port Credit after my wife came over [from Italy]. We rented a home. So, I went to work on a bicycle from Port Credit to Cooksville. There was only two lanes [in the road]. I remember going down in the early morning. We used to start work at seven o’clock in the morning. I had to get up at six o’clock to go three kilometres away, three miles with the bicycle. Probably only about two or three cars go by you in a half an hour ride.”

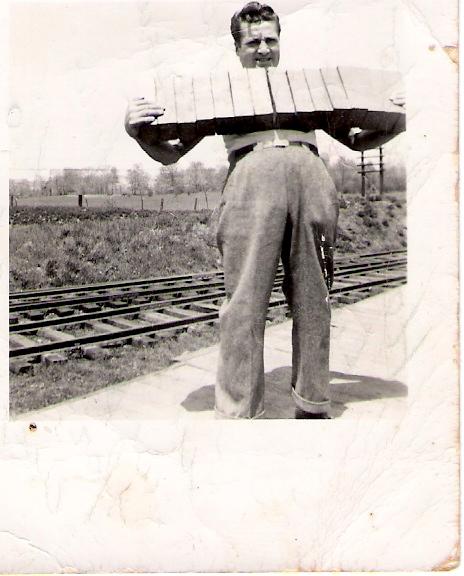

In those early days in Canada working at the Cooksville brickyard, life was hard. Still struggling with Canadian winters, Angelo remembers, “I remember going to the plant. […] There were bricks outside, with about three feet of snow on top of the bricks. There was a big long [line]. We loaded brick from the yard onto the truck. […] That was my job, loading brick all day. Oh, imagine that. It was terrible outside, 10, 20, 30 below zero. I didn’t have enough clothes at the time. But a friend of mine, he was here before me, he had an old coat and a pair of high boots. So, I got by on that. Boy, it was cold. If I wasn’t married and was all by myself, I would have gone back to Italy”.

To make ends meet, Angelo began cutting hair in his spare time. “I remember in the lunch period we had an hour time for lunch. At lunch period I never ate, I had to take advantage of it. I had four people in one hour. I cut four heads. So, it was 40 cents at the time for a haircut. It was money, that was good. See, those years there was no tax. Whatever you buy there was no tax. […] So, I got a little bit of money. […] After that, I bought an old Dodge in 1950,” remembered Angelo. “It was a big help, honestly. I had people from Toronto coming down because the style of cutting hair was just terrible here. There was no style whatsoever. So, the people there, you know, they had a girlfriend or whatever and they came over to see me. The barber in the area was complaining so much they sent the police over,” Angelo laughed. “Well, I did not stop. I only slowed down a little bit. I didn’t want to stop, that was my trade, you see”.

“Eventually, years went by,” Angelo continued, “Everybody worked pretty hard at the time. They bought any home available, no matter how old it was, just as long as the price was good, and it had a roof on it. […] You have to take care of your own home and your family”.

With the weight of caring for his family, Angelo had finally found a calling at the brickyard.

“As a child and young man growing up in Azzano, Italy, I was constantly surrounded by the art of my forefathers. Almost immediately [upon arrival in Canada], I began to experiment with clay and clay brick sculpture [at the brickyard],” recalled Angelo. “By working there in Cooksville, making bricks, I happened to get the clay in my hand and started to make flowerpots, jewelry boxes out of clay. I found it very interesting.”

In between work, Angelo Belluz invested in his artistry. Angelo recalled, “I went to night school for many years. I took, actually, sign painting. […] I used to do the signs on stores and on trucks for companies. I enjoyed doing that. Then I was interested in seeing the stained-glass churches, the windows.

So I went to school for two years to learn how to cut the pieces of glass and put them together to create some art like that. Then I went to school for painting. I remember the high school at Port Credit. I went a couple of times a week. I did work on the wheel, for pottery,” Angelo laughed, “Then I took a course on how to do wiring, electrical wiring”.

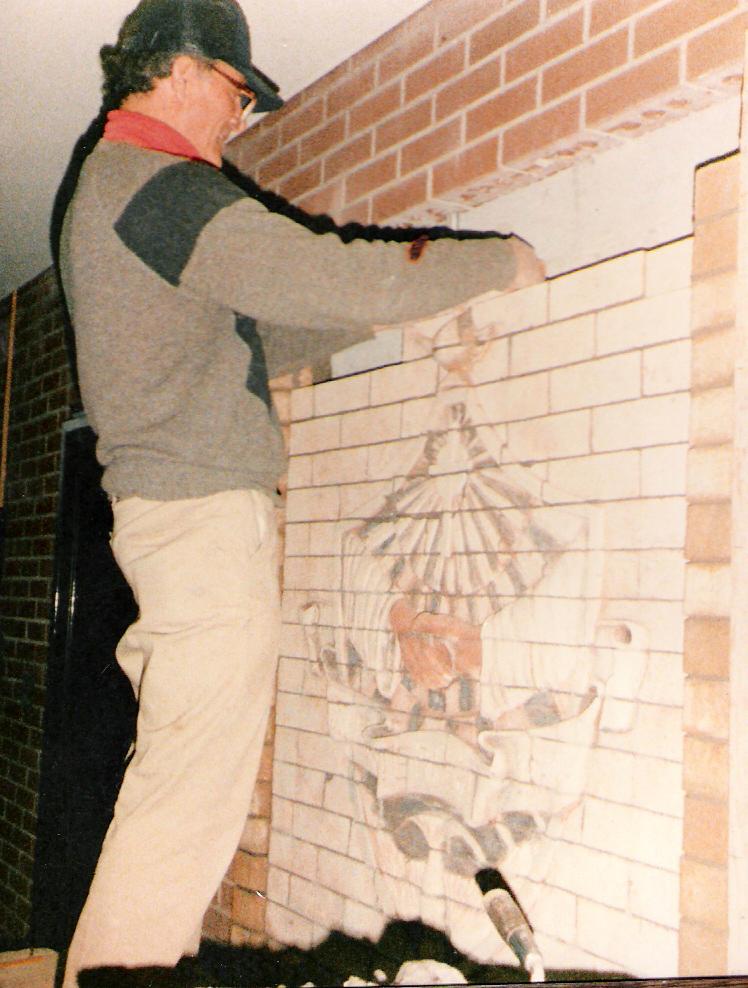

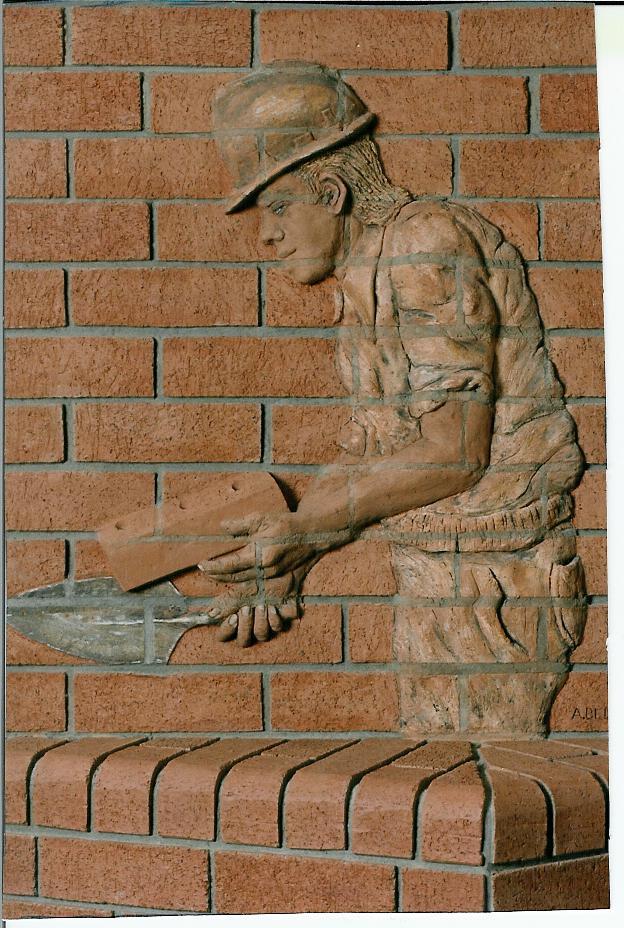

Though Angelo was a man of many talents, it was his sculpting that began to attract the attention of his superiors at the brickyard. Belluz remembered, “I started to make sculptures of my own. My boss at the brickyard wanted to see what I was doing there. He thought it was interesting, creating birds by bas relief […] on bricks of clay. Then the next day he came up to me and asked if I wanted to do that. I said, “Why not?””.

This was his moment to prove himself and his skill, so the first sculpture he made was something close to his heart, something he would have likely seen living in Port Credit. “[My first sculpture was] a crane. I designed that myself. I love birds. They are incredible. The contractor was a builder who buys a million bricks from the brickyard. He wanted me to do it for his home, for his fireplace,” recalled Belluz.

That was the beginning of a lifelong passion for Angelo. “Any time [I had] available, I got the clay the way I wanted it and started making stuff with my hands,” he explained. “That was the beginning. […] Then from there was a spark.

[My bosses] said, “Hey, we’ve got something here.” Then they put me doing that in a studio, a big room for my own. They had orders for me. The architects prepared me a sketch sometimes. They gave me an idea of what it was going to be. I enlarged it from the sketch, one way or another.

But the main idea came from the architect because all the sculptures had to have a particular meaning for the school, for the Board of Education. I put my spark in there, my own way. […] One thing led to another, and I started to doing bigger stuff. Then there was no end to that. […] They gave me other type of work, some designs, some coat of arms, some faces of animals, even portraits. In a short time, he called some architects over to see what I was doing. He got a demand to do bigger ones. So, there was no end to that,” Angelo recalled.

Over the years, the brickyard changed hands multiple times. From Laprairie Brick to DOMTAR and then in 1985, DOMTAR sold out to Canada Brick. “Canada Brick and the DOMTAR people we found a big difference. Canada Brick was more understanding to the worker,” explained Angelo, “We get parties once and twice a year, which we never had before. For me, I found it was a wonderful company”. Overall, Angelo was lucky, he had the support of his superiors and his friends at the brickyard, “I was very fortunate to be with Canada Brick as an older man, working for them I had a great respect. They were fantastic. They treated me very well”.

“When I started doing sculptures, I had lots of friends, because everybody wanted something,” Angelo laughed. The sculptures were so popular that Angelo recalled, “instead of spending one day doing one, I spend two days doing three!”

Angelo explained his process, which took skill, hard work, and years of practice to master. “Brick is made from the machine,” Angelo explains, “It is very solid clay. […] It is very hard to put your fingerprint on it, but if you [try,] it gets a little softer. […] I had a machine [to] slice them. I make seven slices out of one brick. So I put the slices on plywood on the wall, one on top of the other and I create 2 x 2 feet, with four or five bricks perhaps. After I start to stick more brick on it. You have to bang it with a hammer to create the nose, the head of the [figure], or another part of the body, whatever, to get the three-dimension. Then, the small detail [and] you are partly finished,” explained Angelo.

“As my style evolved, I began to apply various oxides and pigments to the clay prior to firing, using some of the knowledge I had gained as a painter of water colours. […] I use the colour powder. […] You mix it with water and paint the face, or the feathers. After that is finished you dry them. They air dry. When that is very dry, you put it through the kiln and fire it. All this colour maintains there like a glaze. This colour is permanent. It won’t disappear. […] [The kiln] is probably about 2000 degrees, 1850, 1900. I think it is very hot…” described Belluz.

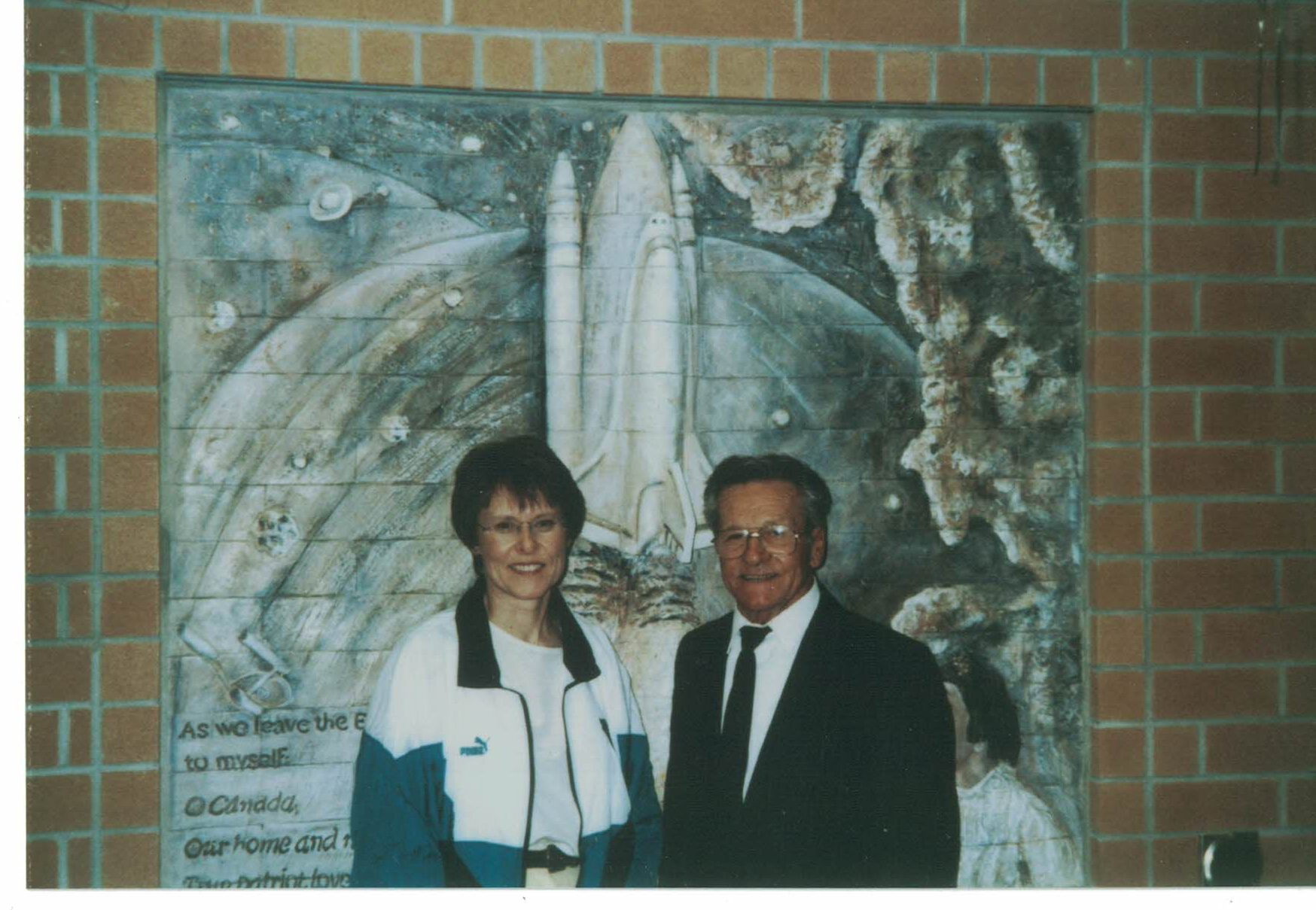

“The result is a rather non-traditional style of brick sculpture, examples of which can be found throughout Canada and the United States in commercial, institutional and residential settings,” explained Belluz.

Angelo Belluz’s artwork can be seen on our own landscape here in Mississauga as well. Perhaps the most iconic of his sculptures is his Streetsville Founders Bread and Honey sculpture, which now sits at Streetsville Memorial Park.

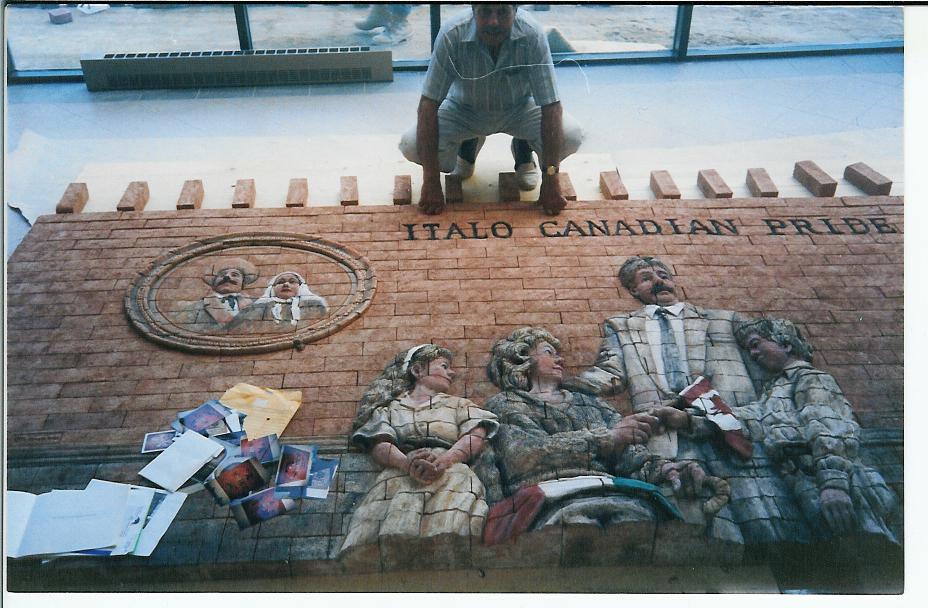

Angelo recalled the iconic artwork saying, “Do you know the politician there, Nando Iannicca? He was one of the councillors who wanted to put up a monument by the arena. So, he came up to me. He said, “What kind of image will be in there?” He said that they would like to have it, going back a few years, as a family coming here from Europe or somewhere. Then there was a lady there from the association of the Bread and Honey Festival. […] She came down to see me [and] showed me the picture of a family with a mom and dad, and a couple of children, a boy and girl, dressed in the costume from the 1800s”.

Angelo was lucky that his superiors supported and encouraged his art. Angelo remembers, “Canada Brick asked to do it in the brickyard. […] Canada Brick was quite happy to get involved because they had a manufacturing plant in Mississauga. Then we did it and it was beautiful”.

By the end of his career, Belluz had created over 500 sculptures. After his retirement from the brickyard, he unfortunately had to give up his trade for the most part. “I kind of let go because you need the other part of support, the firing, sanding. It is a big job. […] I had to give it up,” lamented Belluz. However, he did continue on a small scale in his own home. “I can look [at the sculptures], and refresh them sometimes. Put some more marks on them,” Angelo explains.

Those “marks” were his spark, after all. Perhaps it was this spark that made so many of his pieces unique and special. Angelo put himself in each of the pieces. Angelo Belluz passed away in 2014 in Mississauga, the city he had learned to call home. Belluz’s legacy can be seen in so many buildings, parks, business, and homes, his artistic fingerprint seen across Mississauga and the country.