Justine Welburn

Carrying What Was Always There

A HERITAGE MISSISSAUGA PROFILE ON JUSTINE WELBURN

WRITTEN BY: MEGHAN MACKINTOSH

“Where are you from?” is a harder question than it sounds.

For Justine Welburn, the answer has never been simple. She was born in Victoria, British Columbia, but lived there only briefly. Her family moved often. Calgary. Ottawa. Edmonton. Halifax. Eventually, Mississauga.

“My origin story is pretty long,” she says. “That’s probably the hardest question you could ask me.”

Mississauga is where she has lived the longest. It is where her children grew up. It is where her adult life unfolded.

But the deeper story is not really about geography.

It is about continuity.

Justine & her mom in Calgary

Knowing Before the Word

Justine grew up in Calgary. Some of her earliest memories are grounded in land and in elders. Her family lived next to a long-term care home, and the seniors there became part of her daily world.

“They used to sneak treats through the fence for my sister and me,” she remembers. “That’s where I fell in love with seniors.”

Indigenous identity was present long before it was named.

“What my mom always says is, we didn’t really know there was a word for it,” she explains. “When you’re growing up, it’s just growing up. You don’t ask, ‘Where am I from?”

The values were there. The customs. The way people related to one another.

No one stopped to define it.

Finding Proof in the Archives

As a teenager in Ottawa, Justine became drawn to genealogy. She spent hours in the National Archives, scrolling through microfiche and learning how to read the past through documents most people never see.

“This was before Google,” she says. “You had to take the tape off the shelf, put it in the machine, and just start looking.”

She loved the search itself.

“Finding a name, finding a record, that was my dopamine,” she says. “That moment where you think, this person existed. This is proof.”

Over time, a fuller picture emerged. Her lineage traces back to the fur trade era, to Scottish and English men who worked for the Hudson’s Bay Company and married Cree women. Their children were raised by Indigenous mothers while their fathers moved between continents.

“They’re in the history books,” she says. “I can open books on the fur trade, and sometimes the rebellion, and my family’s in there.”

Seeing names, handwriting, journals, land scrips.

History stopped being abstract.

“I couldn’t believe not everybody was excited,” she laughs. “I was obsessed.”

Care as a Way of Knowing

Justine studied social science, Indigenous studies, and later gerontology. Her professional life took shape in long-term care, where she spent nearly two decades in leadership roles across Mississauga and Toronto.

“For me, care has always been about knowing people,” she says. “What scares them. What comforts them. What they’ve been through.”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, she stepped into crisis leadership at a long-term care home that had experienced devastating loss.

“It was incredibly hard,” she says. “But also meaningful. You do what you have to do for people.”

Even then, the same principles guided her.

“I’ve benefited from being white-passing my whole life,” she acknowledges. “I know that.”

She saw how trauma, racism, and mistrust shaped people’s experiences with healthcare. How those histories didn’t disappear when someone walked through a hospital door.

Culture as Medicine

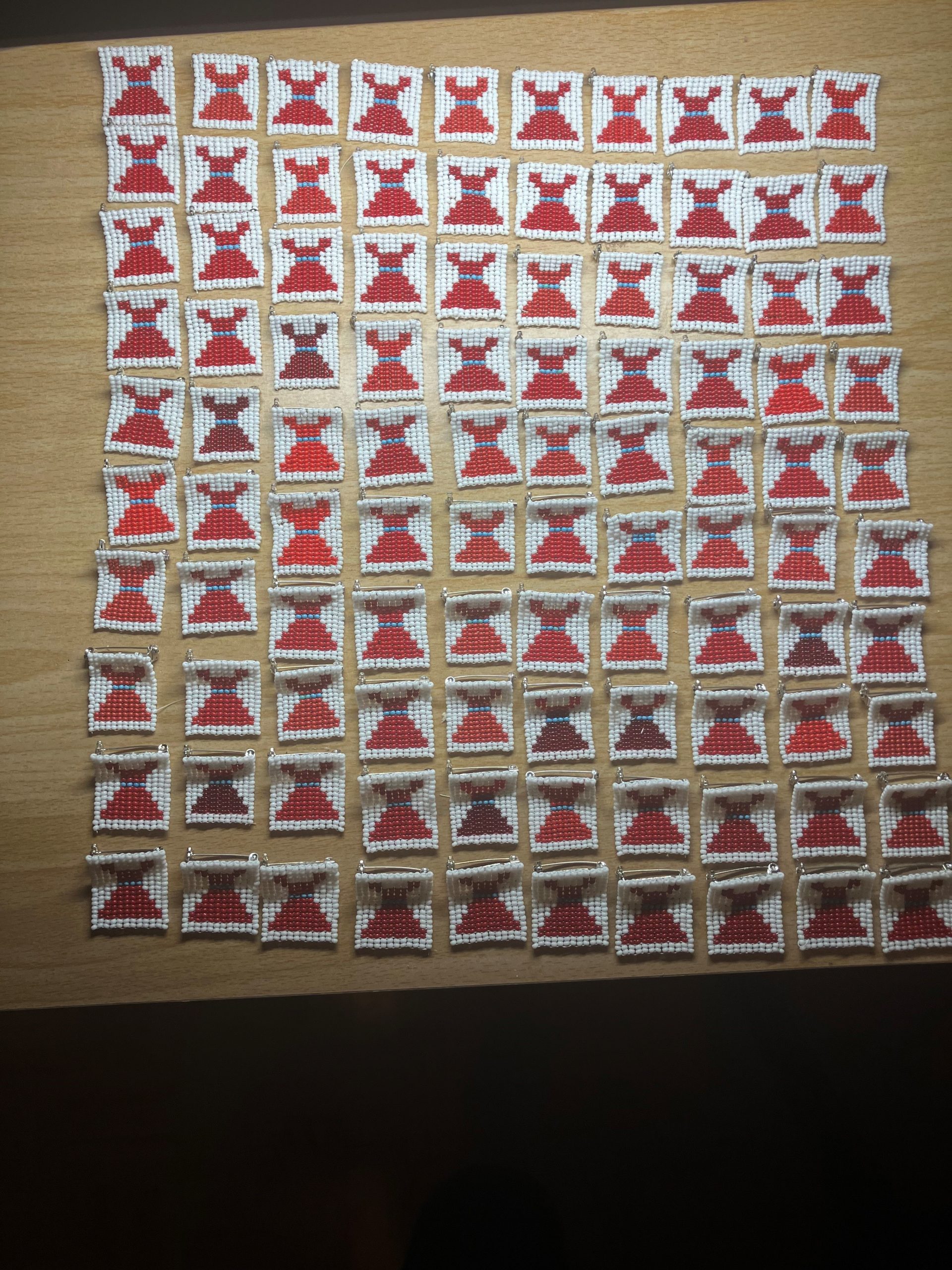

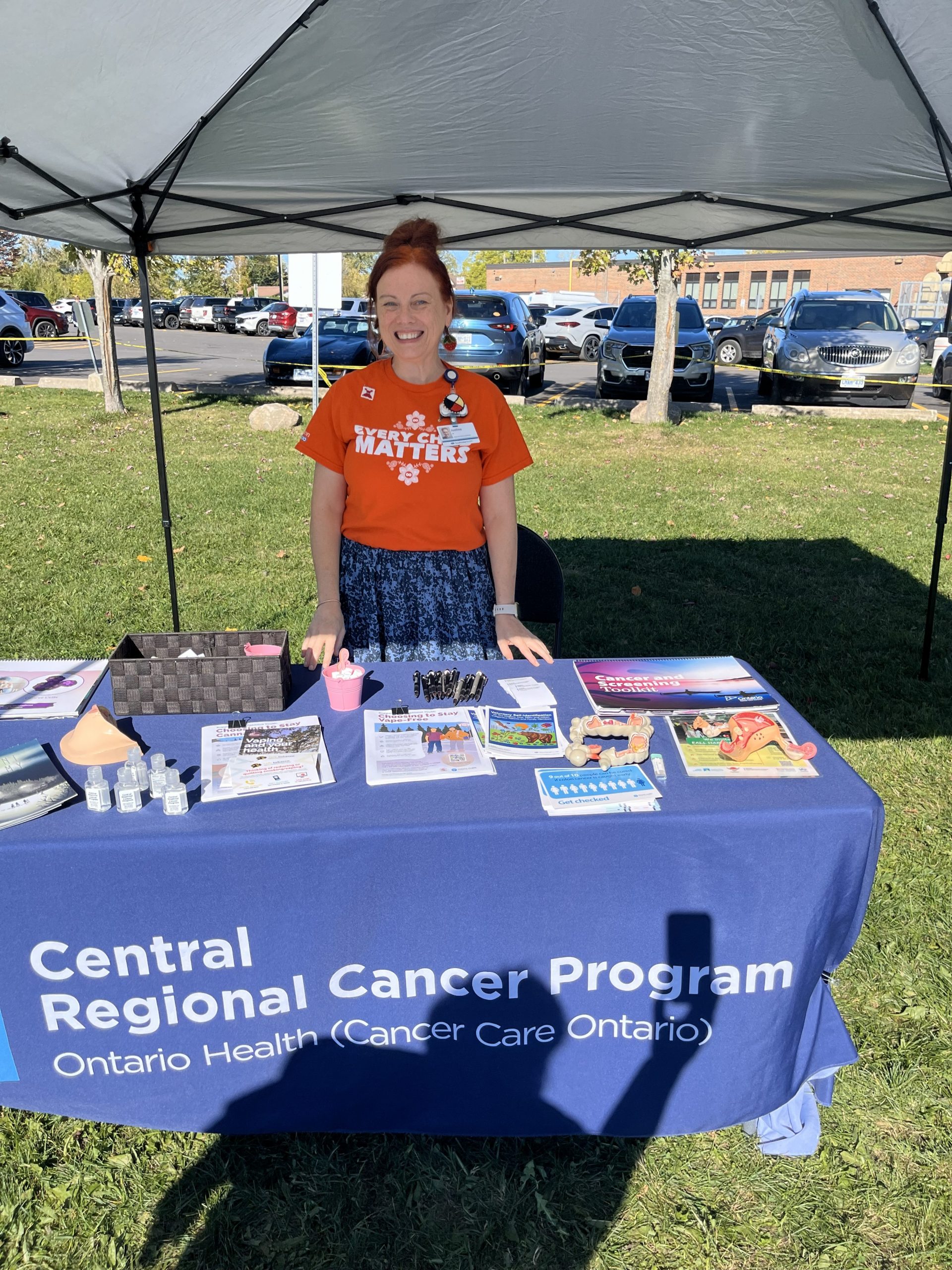

Today, Justine works as an Indigenous Project Coordinator within a regional cancer centre.

“So many people don’t trust the healthcare system,” she says. “And when they do come in, the cancer is often much further along.”

In this work, ceremony is not symbolic. It is practical. It is grounding.

“Every meeting we go to, there’s usually a smudge,” she says. “And at the end, everyone says, ‘I needed that.”

There is a phrase she hears often.

“Culture is medicine,” she says. “And it really is.”

Smudging. Drum circles. Language. Food. Presence.

Not instead of treatment, but alongside it.

Reconciliation, Slowly

For Justine, reconciliation is not something you complete.

“Until Indigenous people have the same quality of life, health outcomes, and life expectancy as everyone else, reconciliation isn’t done,” she says.

She is honest about how slow institutional change can be.

“They tell us not to expect to see it fully realized in our lifetime,” she says. “But that doesn’t mean you stop.”

She also speaks carefully about Métis identity, and about who gets to define it.

“That idea of blood quantum, or proving how Indigenous you are, that came from the government,” she says. “It’s not where your heart is.”

What Is Carried

Justine carries a sash given to her in the mid-1990s, when she first worked with the Métis Nation of Ontario.

“At the time, sashes were really hard to come by,” she says. “It was such a privilege to receive one.”

She owns several now, marking different moments in her life.

That first one still matters most.

She also carries a small bundle. Inside are medicines given to her over time. Sage. Sweetgrass. Cedar. Tobacco. A feather.

“I don’t smudge to explain it to anyone,” she says. “I smudge to slow down. To set intentions.”

Her life has been shaped by movement.

By learning.

By care.

Some stories don’t disappear.

They keep going, whether we name them or not.