Clayton Cadeau

Clayton Cadeau and the Responsibility of Remembering

A HERITAGE MISSISSAUGA PROFILE ON CLAYTON CADEAU

WRITTEN BY: MEGHAN MACKINTOSH

Clayton Cadeau often says that ceremony begins before anything visible happens. Before the fire is lit. Before people gather. Before words are spoken.

It begins with an open heart.

For Clayton, that openness is not symbolic. It is a way of moving through the world.

Over many decades, through work, family, ceremony, and community, he has learned that knowledge arrives slowly and is carried through relationship. Some teachings are spoken aloud. Others are held quietly. Many were once hidden for survival.

His story reflects that layered inheritance.

What Was Hidden

Clayton was born in Toronto and raised in a large family. He knew from a young age that he was Métis, though it was not something discussed openly.

“I was around six or seven years old,” he recalls. “My grandfather told me. He said, ‘You’re mixed blood.”

The knowledge existed inside the family, but it lived carefully. Clayton’s grandmother, who was Métis, had been sent to residential school in the north. The effects of that experience shaped the generations that followed.

Like many Métis families in Ontario, survival meant discretion. Language was set aside. Cultural practices were kept out of public view. Even within extended family networks, identity was not always shared.

Clayton explains it plainly:

“Ontario really had to hide it. You didn’t get jobs. You didn’t get opportunities. So everything you tried to keep to the side. Even when my dad worked at the post office, if someone asked if he was Métis, he’d say no. He’d say he was French or Italian. That’s how you survived.”

In Toronto’s public school system, Indigenous history was largely absent.

What Clayton learned came instead from grandparents, from fragments of family memory, and from an early sense that something important had been deliberately left unsaid.

Learning Outside the Classroom

Clayton’s understanding of Métis identity developed gradually, shaped less by institutions than by listening.

In his mid-thirties, encouraged by a cousin, he began the process of formal recognition. Together with family members, he helped establish the Credit River Métis Council more than twenty years ago. The work was not about status, but about learning who they were and where they came from.

“There was nothing taught about us,” he says. “So we learned from elders.”

Those teachings revealed how Métis culture adapted under pressure. Music and ceremony survived by changing form.

Drums were hidden. Fiddles were accepted.

Clayton explains that in earlier generations, carrying or playing a drum openly was often not safe. Families protected what they could by adapting how teachings were shared.

“The fiddle was the instrument that became the foundation for the Métis,” he says. “It could be played without fear.”

Through the fiddle, older songs continued to live. They were often played in rounds of four, honouring the four directions and the heartbeat of Mother Earth. In this way, teachings and rhythms endured, even when the grandmother drum itself had to remain hidden.

Today, Clayton says, that has changed.

“The grandmother drum can be played with honour now,” he explains. “Those songs don’t have to stay quiet anymore.”

For him, this shift is not simply about revival, but about continuity. What was once protected through adaptation can now be shared openly, carried with respect, and passed forward.

Walking the Spiritual Path

Clayton speaks carefully about spirituality. Some things, he says, are not meant to be explained publicly.

What he will say is that his path has been shaped by humility and by time. Over many years, through relationships built slowly, he was welcomed into circles of elders. That welcome was not something he sought.

“You don’t decide you’re an elder,” he says. “You’re welcomed. And even then, you’re still learning.”

That welcome came through Elder Joseph Paquette, a Métis elder Clayton worked closely with for many years. Elder Joseph was deeply involved with Heritage Mississauga, and played a central role in bringing Indigenous ceremony and teaching into the space with care and consistency.

It was Elder Joseph who first introduced Clayton to elders at Serpent River First Nation, where Clayton was welcomed into a circle of elders. That acceptance, he says, was a profound honour, and marked a turning point in his life. It was there that he began learning about ceremony, not as something to perform, but as something carried through responsibility and relationship.

Elder Joseph passed away in March 2020. Clayton continues to speak of him with gratitude, recognizing his role not only as a teacher, but as someone who opened doors and trusted him to walk the path with humility.

For Clayton, ceremony is not performance. It is responsibility. When asked to explain it, he returns again to openness:

“The only thing we ask is no alcohol. That’s it. Come with an open heart. We honour all. That includes nature, all animals. Everything has a spirit. When that fire is lit, we’re opening the line. What happens after that is between you and Creator.”

Elder Joseph Paquette, who passed away in March 2020, played a key role in Mississauga’s heritage community and introduced Clayton Cadeau to the Circle of Elders at Serpent River First Nation.

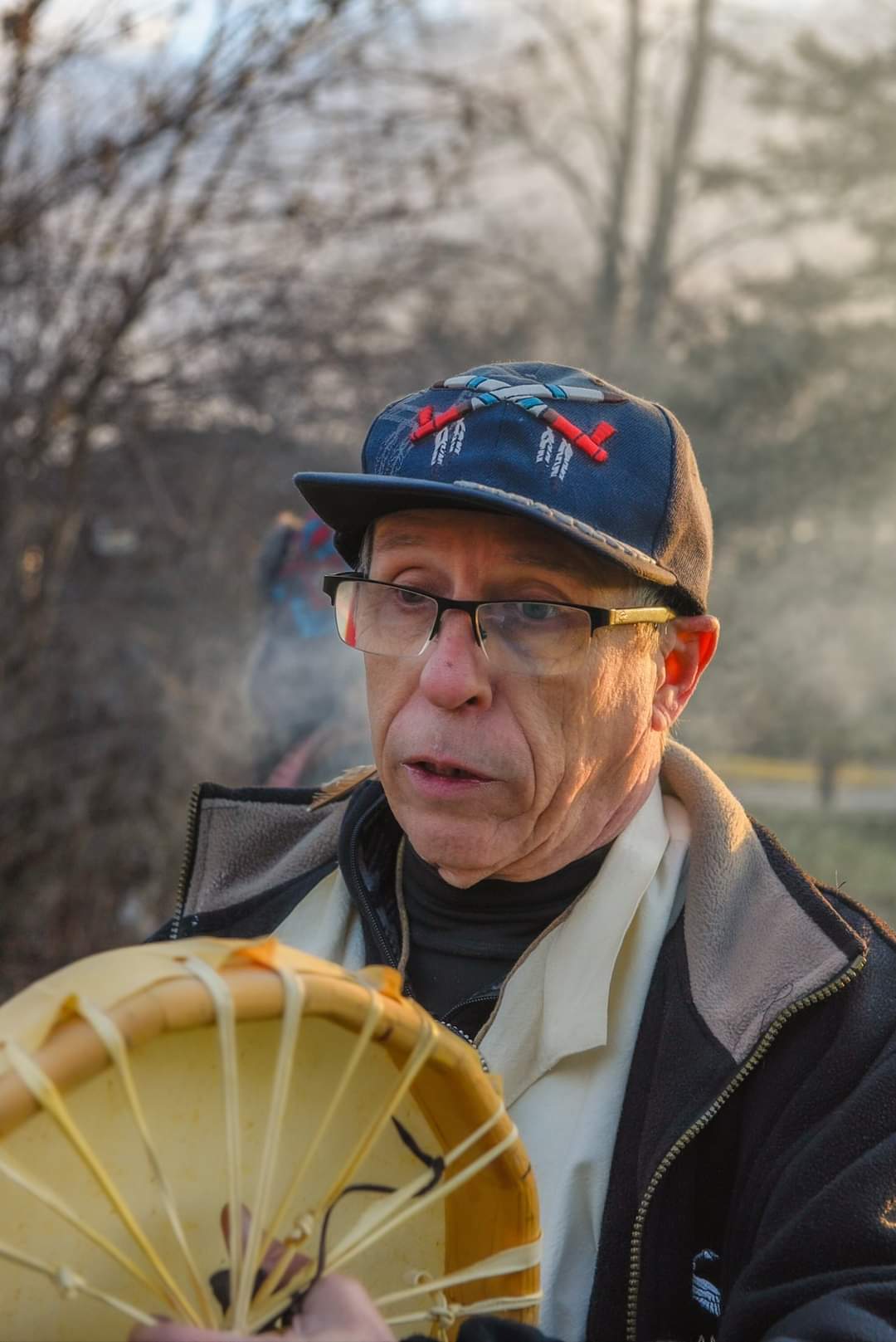

Elder Clayton Cadeau at Heritage Mississauga.

Community, Ceremony, and Mississauga

Clayton’s connection to Mississauga grew through collaboration and shared work. Through Indigenous networks and long-standing relationships, he became involved in ceremonies held in the city, including seasonal and sunrise gatherings that continue today.

His work with Heritage Mississauga developed over many years, grounded in mutual respect.

“What I felt here was openness,” he says. “A willingness to listen.”

The ceremonies held in Mississauga are not demonstrations. They are living moments of continuity, where people gather to mark seasonal change, honour ancestors, and acknowledge shared responsibility to the land.

For Clayton, this is living heritage: practiced, relational, and carried forward.

Continuity

As elders age and pass on, Clayton is conscious of what can be lost.

“Our elders are passing away, and knowledge is not being passed. When that knowledge is lost, it’s lost forever. That’s why people have to step up. It’s a humble path, and it’s not an easy one.”

Still, he believes continuity exists beyond words. Teachings remain in how people show up for one another, in patience, in listening, in small acts of care.

“Sometimes it’s just saying hello,” he says. “You don’t know how long someone has gone unseen.”

Remembering, for Clayton, is not about reclaiming what was taken. It is about carrying forward what was entrusted, walking alongside others, and keeping the path open.

No one walks alone.