Part 1: Treaties

Searching for the Mississauga of the Credit River: Treaties

By Meaghan FitzGibbon

During this past school year I had the opportunity to participate in an internship at Heritage Mississauga through the Environment program at the University of Toronto Mississauga. My position as First Nations Treaty Researcher was envisioned by Historian Matthew Wilkinson and designed to expand on our knowledge and understanding of the Mississauga First Nations, who called this area home for over 200 years.

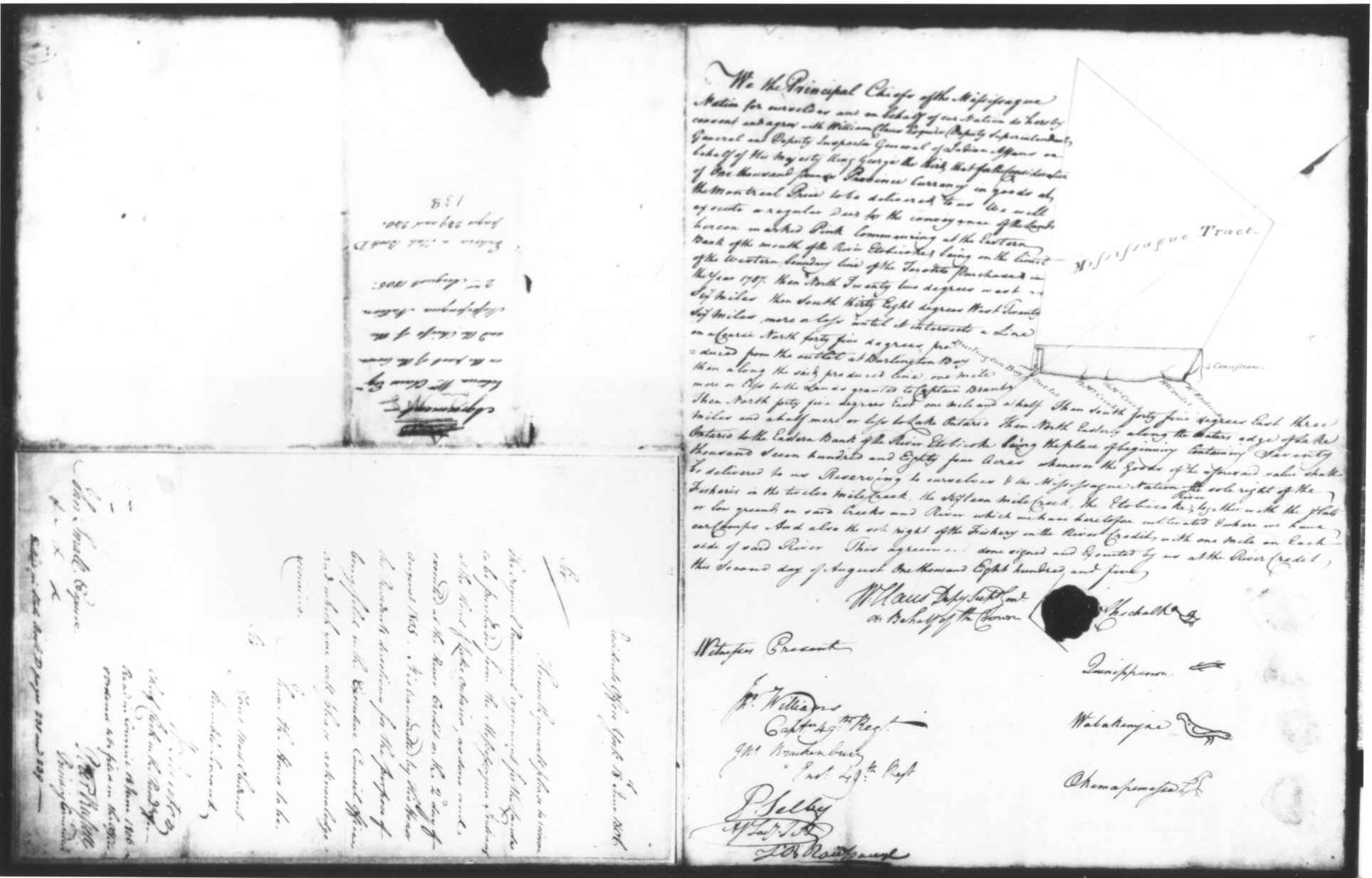

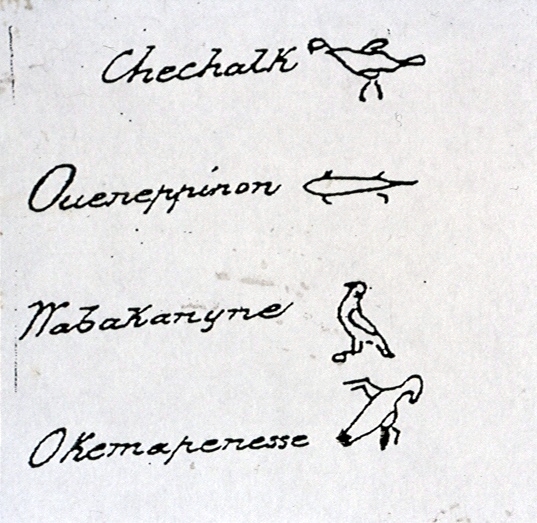

In 2005, Heritage Mississauga began an in-depth research project of the “First Purchase” or Treaty 13a in preparation for the 200th anniversary of this area being opened for settlement. The subsequent treaties (19, 22 and 23), however, had not been as thoroughly researched. The purpose of my study was to provide a greater historical understanding of these lesser documented treaties, as well as to determine their effect on the Mississauga Nation before their relocation in 1847. The intention being to provide a greater understanding of the historical development of the City of Mississauga, the Mississauga Nation at New Credit and modern treaty claims.

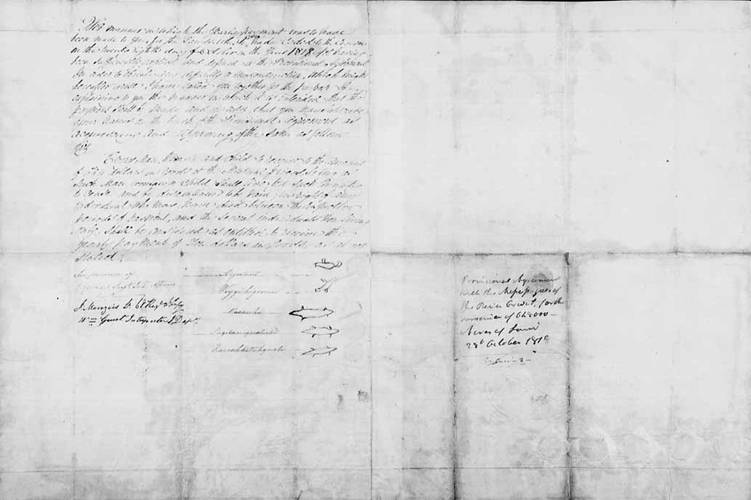

The first treaty I researched was Treaty 19. On October 28, 1818 the Mississauga First Nation ceded the land north of modern day Eglinton Avenue to the British Crown. This area became known as the “New Survey” in the Township of Toronto. This area included the villages of Streetsville, Meadowvale and Malton. The Mississauga Nation kept three portions of land on the Credit River (also known as the Credit Indian Reserve), and the Twelve Mile and Sixteen Mile Creeks, which the Mississauga First Nation had previously been retained in Treaty 13a.

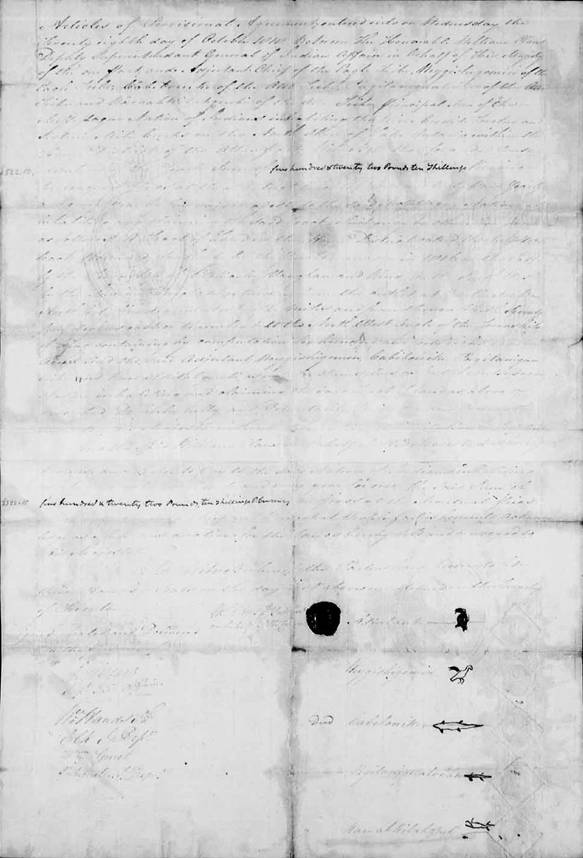

Two years later, the Government negotiated for these lands as well; new settlers in the area wanted access to the creeks and river to establish mills. On February 28th, 1820, Treaties 22 and 23 were signed. These treaties divided the land in a peculiar fashion. Treaty 22 surrendered all the land from the modern day Queensway to Lake Ontario, and from approximately the northern entrance of the University of Toronto Mississauga/ Harkiss Road to Eglinton Avenue (within the one mile on either side of the Credit River), as well as the lands at the Twelve and Sixteen Mile Creeks. Treaty 23, signed the same day, surrendered all the land between the portions surrendered in Treaty 22, this being the land on either side of Dundas Street. This left the Mississauga Nation with only two hundred acres on the east side of the Credit River.

One possible explanation for the nature of the division between Treaty 22 and 23, was provided by Donald B. Smith, an authority on the Mississauga Nation, who proposed that the middle portion was negotiated a year earlier in 1819. This suggests that the land was surrendered earlier but the treaty was not written and signed immediately. The importance of the middle section to the British is understandable because it would include Dundas Street a major road even in the early 19th century. The majority of the middle section was given to Major Thomas Racey to establish a village and mill. This section is still known as the Racey Tract within the City of Mississauga. This land was surveyed and settled almost immediately while the northern and southern sections were retained. Today the majority of the University of Toronto Mississauga is within the Racey Tract as well as the Grange (the office of Heritage Mississauga) and the village of Erindale.

The most intriguing aspect of the project was the connection between the structure of the treaties and the impact on the lives of the Mississauga at the Credit River including their decision to leave the area in 1847. It is generally believed that the Mississauga surrendered their land in three separate treaties over the course of the 15 years from 1805 to 1820 with the exception of the 200 acres they kept on the Credit River where they set up a village. It was discovered, however, that the land was actually surrendered during this period in four treaties: Treaties 13a, 19, 22, and 23. Also, after 1820, the Mississauga were not living on the 200 acres they had retained, but on land they had already surrendered in Treaty 22. The Credit Mission village was on the opposite side of the River from the 200 acres they had retained. Yet, for years the government held the majority of the land on the Credit River and the Twelve and Sixteen Mile Creeks as Crown Reserves. Only a portion of the land on the Credit River, situated on either side of Dundas Street, was sold for the purpose of building a village for non-aboriginal settlers. This was a strange turn of events, considering the reason the government wanted the land was for the use of the river and creeks.

Sources:

Canada. Indian Treaties and Surrenders: Treaties 1-138. vol.1, 1891, reprinted 1992.

Gibson, Marian M. In the Footsteps of the Mississaugas. Mississauga: Mississauga Heritage Foundation, 2006.

Jones, Peter. Life and Journals of Kah-ke-wa-quo-na-by (Rev. Peter Jones). Toronto: Anson Green, 1860.

Land Abstracts. Region of Peel Land Registry. (microfilm)

Mathews, Hazel C. Oakville and the Sixteen: The History of an Ontario Port. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1953.

Pope, J.H. Historical Atlas of Peel County, Toronto: Walker and Miles, 1877. Facsimile reprinted in 1971.

Smith, Donald B. “The Dispossession of the Mississauga Indians: A Missing Chapter in the Early History of Upper Canada.” Ontario History LXXII (June 1981).

—. “Their Century and a Half on the Credit.” In Mississauga: The First 10,000 Years. ed. by Frank A. Dieterman. Toronto: Mississauga Heritage Foundation, 2002.

—. “The Mississauga, Peter Jones, and the White man: The Algonkians’ Adjustment to the Europeans on the North Shore of Lake Ontario to 1860”. Ph.D. diss. University of Toronto, 1975.

—. Peter Jones, the Mississaugas of the Credit and the Indian Department of Upper Canada, 1825-1847.

Tremaine’s Map of County of Peel, Canada West. G.R. and G.M. Tremaine, 1859