Tee Copenace

Moving Without Leaving: A Life Shaped by Responsibility

A HERITAGE MISSISSAUGA PROFILE ON TEE COPENACE

WRITTEN BY: MEGHAN MACKINTOSH

There is a feeling that comes from growing up on the land. You do not always know how to name it when you are young. You just know when it is gone.

For Tee Copenace, that feeling begins in Treaty 3 Territory. Her early years were spent on her First Nation community, close to the Winnipeg River, in a place where children left the house in the morning and came home when the light was fading.

“You didn’t come back until the sun was going down,” she says.

Bikes, water, forests, and roads shaped the rhythm of the day. Freedom was ordinary. So was belonging.

Only later would Tee understand how much those early experiences mattered, or how much the land beneath them had already endured.

Winnipeg river and community drum. Photo Credit: https://www.naturescapephoto.ca/

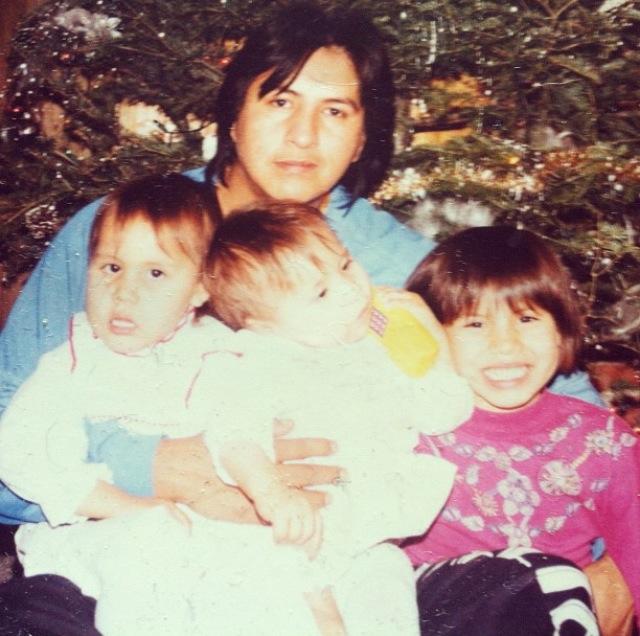

Family and the Good Life

Tee grew up in a large, blended family where siblings were simply siblings. There was no dividing language. Family was family.

Her parents lived what she describes as mino-bimaadiziwin, the good life. Not as an idea, but as a way of being. Both worked in social services, supporting Indigenous families and community members in different capacities.

“They lived the good life,” Tee says. “And I’ve always wanted to make them proud.”

Her mother worked across justice, child protection, and community supports. Her father worked in housing and later at Lake of the Woods District Hospital, supporting Indigenous patients and families and offering cultural connection and translation in Anishinaabemowin.

Care was constant. So was responsibility.

The house was often full. Alongside her siblings, Tee’s parents were foster parents, welcoming children into their home for short periods of time. People came and went. The family adjusted.

“It was loud. It was busy. That was normal for us.”

What Tee understands now is that she was learning, early on, that care does not require permanence to be real.

Leaving the Community

When Tee was still young, her parents made the decision to move the family off the reserve.

At the time, she did not understand why.

There had been conflict in the community. A blockade was set up at the entrance to the reserve. Armed, masked individuals were present. School buses were stopped. Children watched quietly.

“I remember being scared,” she says. “But no one explained anything to us.”

Her parents decided it was no longer safe to stay. They moved the family into town.

Though Kenora was only a short drive away, the change was significant. Life on the land gave way to something more contained. Family and community were no longer just outside the door.

“You’re not there when it gets dark anymore,” Tee says. “That changes things.”

Her parents were deliberate in how they made the move. They saved. They bought land. They built a house themselves. Years later, when they paid off the mortgage, Tee understood the weight of what they had done in a way she could not have as a child.

“They worked so hard,” she says. “I didn’t see it then. I see it now.”

Learning What the Land Has Lost

As a child, Tee remembers swimming, fishing, and exploring without knowing the fuller history of the land around her.

She did not learn about the flooding caused by dam construction along the Winnipeg River until much later.

Wild rice beds were lost. Wildlife was displaced. Parts of the community that were once continuous land became islands.

“We were making the best of it,” she says. “But the damage had already happened.”

She speaks carefully about how reserve lands are often perceived from the outside. What looks valuable or idyllic was not freely chosen, and in many cases had already been compromised.

“The land we have wasn’t necessarily our choice,” she says.

While there have been efforts toward repair, including collaborative environmental initiatives, Tee remains measured. Hope, for her, is tied to accountability and relationship, not statements or settlements alone.

School and the Cost of Endurance

School in Kenora came with its own lessons.

Racism was common enough that it became something students were expected to tolerate quietly.

“You just dealt with it,” Tee says. “That was the norm.”

She remembers entering classrooms or social spaces hoping that nothing would be said that day. The anticipation itself was exhausting.

In her final year of high school, Tee nearly missed graduating because of an overlooked independent study course. A guidance counsellor discouraged her from trying to resolve it, suggesting she accept graduating later.

It was another educator, Indigenous guidance counsellor Marilyn Sinclair, who intervened.

She made a plan. She stayed late. She helped Tee finish the course in time to graduate with her peers.

“She believed in me,” Tee says. “That mattered.”

Years later, Tee would return to that moment often, not with bitterness, but clarity.

“I knew I needed to be the person I didn’t have.”

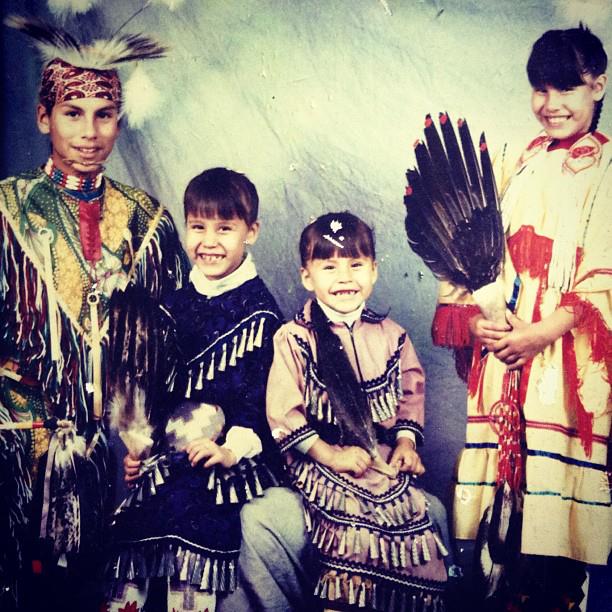

Confidence, Built in Circles

Long before postsecondary education, Tee learned confidence through movement.

She began powwow dancing as a child. At first, she resisted. The arena was intense. But her parents encouraged her to stay.

“You dance for the people,” she was taught.

Over time, the powwow circle became a place of grounding. She learned by watching elders, by listening, by being present. Confidence followed.

“That circle gave me my voice,” she says.

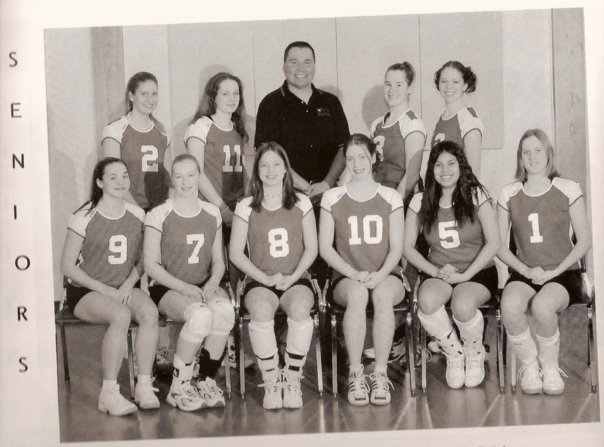

Sport played a similar role. Volleyball, basketball, and especially baseball shaped her adolescence. Athletics brought structure and discipline. Baseball, she learned, ran deep in her family.

“Baseball is in our blood,” her father once told her.

Together, dance and sport taught Tee how to carry herself, how to speak, and how to step forward when needed.

Education as Responsibility

Tee’s path through education was not direct.

She began in Early Childhood Education and quickly learned how demanding the work was. A colleague named Pat pulled her aside one day and spoke plainly.

“You’re not supposed to be here,” she told her. “You’re meant for something else.”

It was not dismissal. It was recognition.

Encouraged to return to school, Tee shifted toward social services and education, guided by a single question: How do I help my people navigate systems that were never built for us?

Her academic journey unfolded across colleges and universities, grounded in a family history shaped by residential school survival.

“I’m the first generation in my family not to attend residential school,” she says.

Education, for Tee, was never about achievement for its own sake. It was about continuity.

Tee Copenace at her Master’s graduation from York University, where she completed her Master of Education in Urban Indigenous Education.

Moving Without Leaving

At eighteen, Tee moved to Australia through a work-study program.

The distance was hard. Money was tight. Homesickness was constant. But she found community where she was not expecting it, through co-workers, roommates, and families who offered care without asking questions.

“You can find family anywhere,” she says.

The experience expanded her sense of resilience and confirmed something she already knew. Movement does not require disconnection.

Today, Tee lives in Mississauga, near the water in Port Credit. The lake offers familiarity. Though she lives far from her home community, her ties remain strong.

She serves on boards. She participates in community governance. She stays connected to family in the north.

“My home will always be Kenora,” she says.

Carrying Forward

Tee understands her life not as a series of departures, but as an ongoing act of carrying.

She carries land memory, family teaching, and responsibility into every space she enters.

There is still work to do. She does not pretend otherwise.

But she remains hopeful.

And she continues, quietly, to move through the world without leaving who she is.